who tells the story?

Image: Mary Little (b. 1786–1871?), sampler, Newburyport, Massachusetts, 1800, Silk on linen, 18 x 22 in., William Butterworth Foundation, Moline, Illinois, 989.108.1. Black servants, enslaved or free, were an assumed part of New England everyday life.

Book review: Jared Ross Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds : A History of Slavery in New England (Amherst: University Of Massachusetts Press, 2019).

People in power have almost always controlled the historical narrative. Recognizing that history related by the powerful only tells part of the story, historians have sought to understand how those without power have exercised their agency to shape their lives and relationships.

In Black Lives, Native Lands, and White Worlds, Jared Ross Hardesty presents accounts of enslaved New Englanders who negotiated power relationships with their masters and created identities beyond that of the enslaved. Without minimizing the cruelty of the system, Hardesty emphasizes the ways that enslaved people defined their lives for themselves.

In his readable, comprehensive history of New England enslavement from the early 1600s to the eve of the American Revolution, a portrait of a people emerges, inviting questions about our social structure and informing our thinking and research about the lives of those on southern plantations.

A portrayal, in retrospect, of the working life of the “plantations” of colonial Rhode Island, a centre of the slave trade and enslavement. WPA artist Earnest Hamlin Baker, "South County Life in the Days of the Narragansett Planters," Wakefield, Rhode Island, post office in ca.1939/40. Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Hardesty begins by exploring the unique nature of slavery in New England. In contrast to the South, slavery in the Northeast lacked a clear legal framework. This absence allowed for the formation of, to some degree, negotiable relationships between enslavers and enslaved.

So, for instance, enslaved people were not always confined to agricultural labor; many became skilled workers, were hired out, or worked for themselves, at times retaining wages with which to eventually buy their freedom. These arrangements, while still deeply embedded in coercion, created space for self-determination and social mobility.

“Enslaved peoples’ literacy had the paradoxical effect of exposing them to ideas about tyranny and revolution“

While religious leaders sanctioned slavery during the 1600s and early 1700s, New England Christian leaders (see our blog post on Cotton Mather and slavery, here) also insisted that enslaved people learn to read and write as part of their Christianization. Literacy intended for reading the Bible had the paradoxical result of exposing the enslaved to Enlightenment ideas about tyranny, revolution and freedom as found in newspapers and pamphlets.

Further, through their proximity to public spaces where political debate took place and printed materials were read aloud, the enslaved heard the ever-more popular revolutionary discourse and discussed it with their families and communities. What, after all, did “liberty” and “freedom” mean if it did not mean freedom for enslaved people?

This political education supported enslaved peoples’ involvement in civic life. They participated in election and muster day events, and they established Negro Election Day, an event in which a black representative was elected. When white authorities imposed restrictions, such as banning the enslaved from attending public talks on tyranny, their actions were largely ineffective because of the pervasive public revolutionary discourse.

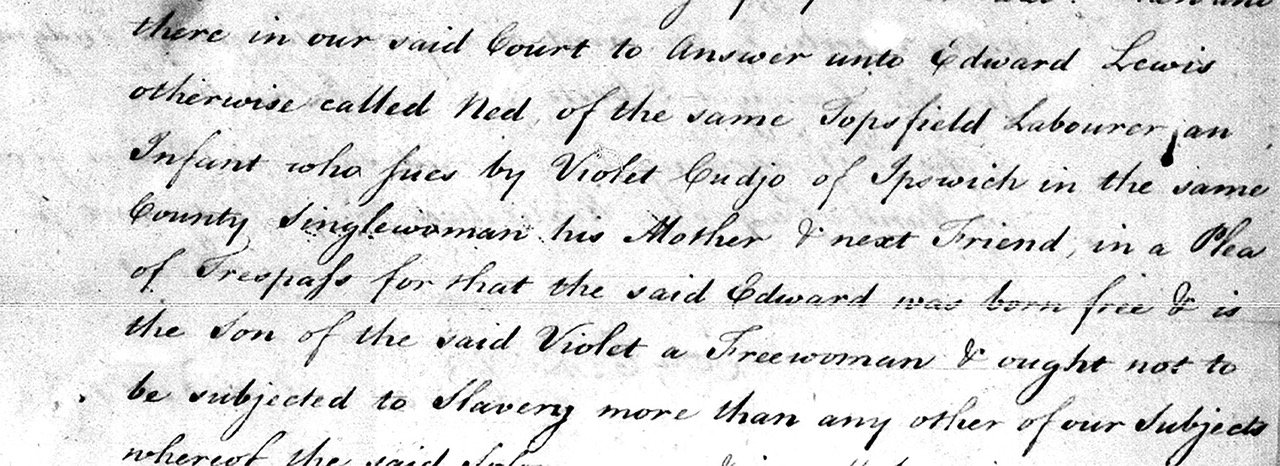

Image: A page from the writ filed on behalf of Edward Lewis, one of the 21 enslaved people in the Revolutionary era who sued for his freedom - and won. Jeanne Pickering

Hardesty shows how the American Revolution became a moment of both disruption and opportunity. Enslaved individuals served in the war, and, after its conclusion, many sought the pensions they were due and pursued judicial emancipation. Their actions during and after the war highlight the complexity of their political engagement and their efforts to define their futures.

What did the Revolution mean for black Americans in the new nation? For Hardesty, the struggle for autonomy and against oppression persisted and even intensified, along with the spread of racist and pseudo-scientific beliefs about black inferiority. For that reason, he says, slavery’s legacy “continues to haunt a region - and nation - to this day.”

“what did ‘liberty’ mean if not freedom for enslaved people?“

But Hardesty also reveals a black American culture that was, and is, resilient and adaptive. He demonstrates how enslaved people built communities and fostered identity despite systemic oppression.

His book is a reminder that we cannot rely on those in power to tell the stories of marginalized groups. We need more work like Hardesty’s to foster a more complete understanding of those who came before us and our nation today.

● To win a copy of Jared Hardesty’s Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds, join our new short essay competition, Why does the 17th century matter?

In a sentence or a few paragraphs (up to 250 words) tell us what you think why the 17th century is relevant today. Evana Rose Tamayo, our new volunteer and author of this review, will select the strongest submissions along with PHB board members. We’ll publish them (in full or in in part) on our website. Please specify whether we can use your name and, if so, whether your full name or just first name. Write to us at phbostons@gmail.com by June 15!

● Watch Jared Hardesty’s presentation, Built from Bondage: Slavery and the Colonization of New England, 1620-1700, the first in in our 2023 lecture series Enslavement & Resistance: Slavery in Early New England, here.

And there’s more…

Richard Boles’ nuanced story of the contradictions of Puritan theologians and the way enslaved people made churches their own in Enslaved Christians: Black Church Members in an Era of Cotton Mather.

Chernoy Sesay Jr. on the eloquent Black Masons’ petitions for freedom before the Revolution, “Petition after Petition”: Boston’s Black Freemasons’ Fight for Freedom, part of our 2024 Tyranny vs Liberty lecture series.