Learn

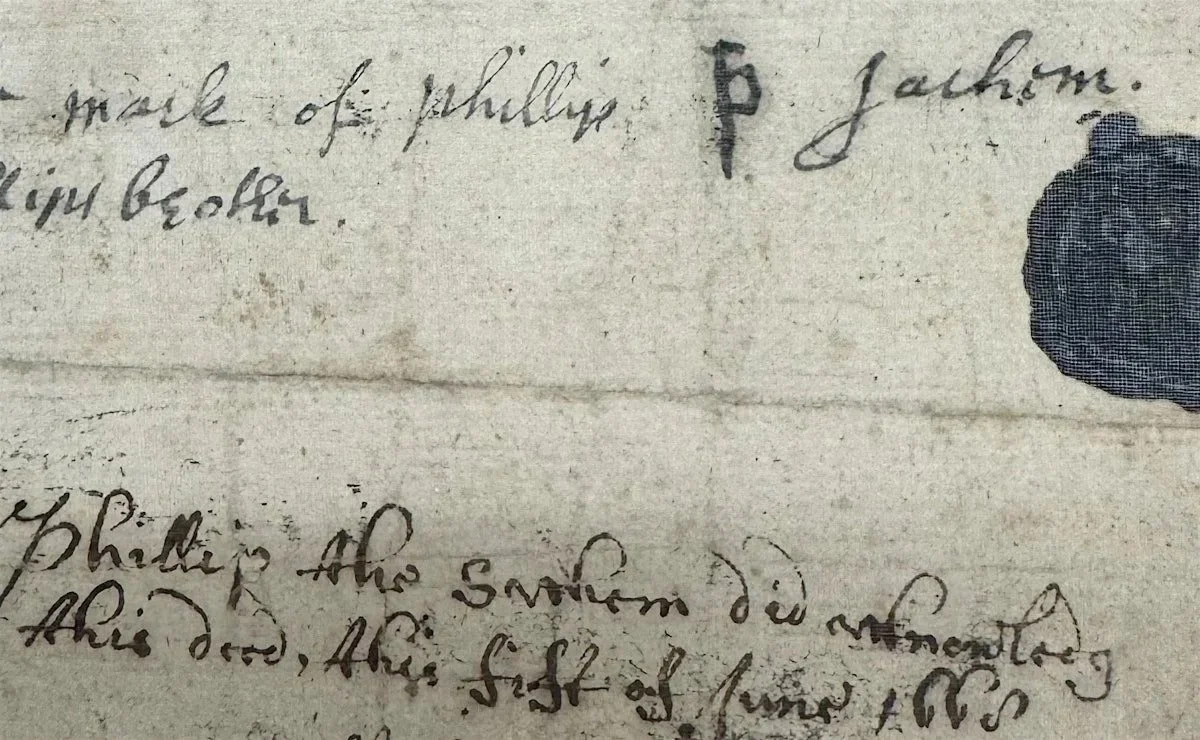

The only known written record, in his own hand, of Metacom, or Philip, after whom the war was named. [Philip, sachem of the Wampanoag. Quitclaim by Philip, Rehoboth, MA], from the collections of the John Carter Brown Library.

metacom’s resistance

Our 2026 series marks the 350th anniversary of one of the most fundamental events of the 17th century in New England: King Philip’s war, 1675-1678. Despite its importance, few of us know of it - or, if we do, it’s likely that we’ve only heard the harrowing tales of English captives, like that of Mary Rowlandson. Colonists were slaughtered, captured, held for ransom and terrorized, with half of all colonial towns destroyed. But the story that’s been told has been almost entirely one-sided. What if, instead of a wanton attack by Indians, we see this another way - as Native resistance to the colonial annexation of land, violation of Indigenous sovereignty, and the destruction of lives and livelihoods? What if we see Philip, who marshalled Indigenous tribes to resist, as a hero, not a “savage”?

Metacom’s Resistance: Retelling King Philip’s War and Its Legacy offers a comprehensive, electrifying picture of this most brutal of wars. From our first introductory lecture in March 2026 to a final reckoning of the war’s legacy with an inter-tribal panel in May, we look at the costs and consequences of King Philip’s War. The series combines lectures with panel discussions, in person events with online presentations, book club discussions of primary sources, and a trip to Turners Falls for a Day of Remembrance.

We are grateful to the historians, tribal preservation officers, independent scholars and tribal citizens who make up this program series. We thank Elizabeth Solomon of the Massachusetts at Ponkapoag; Hartman Deetz, Mashpee Wampanoag; Brad Lopes, Gay Head Aquinnah Wampanoag; Brittney Walley, Nipmuc; David Brule, Nehantic Nation; Liz Cold Wind Santana-Kiser, Chaubunagungamaug Band of Nipmuck Band; Cheryll Toney Holley, sonksq of the Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band; Mack H. Scott II, Narragansett; Paula Peters, Mashpee Wampanoag; and Kimberly Toney, Hassanamisco Nipmuc Band.

We are thankful, too, to historians Linford Fisher, Kevin March and others, and to the partner organizations on this series: Boston Public Library, Cambridge Public Library, Colonial Society of Massachusetts, the Congregational Library & Archives, History Cambridge, and the Nolumbeka Project.

Sign up here for Metacom’s Resistance, as we retell the story of America’s bloodiest war, per capita, in eight thought-provoking events.

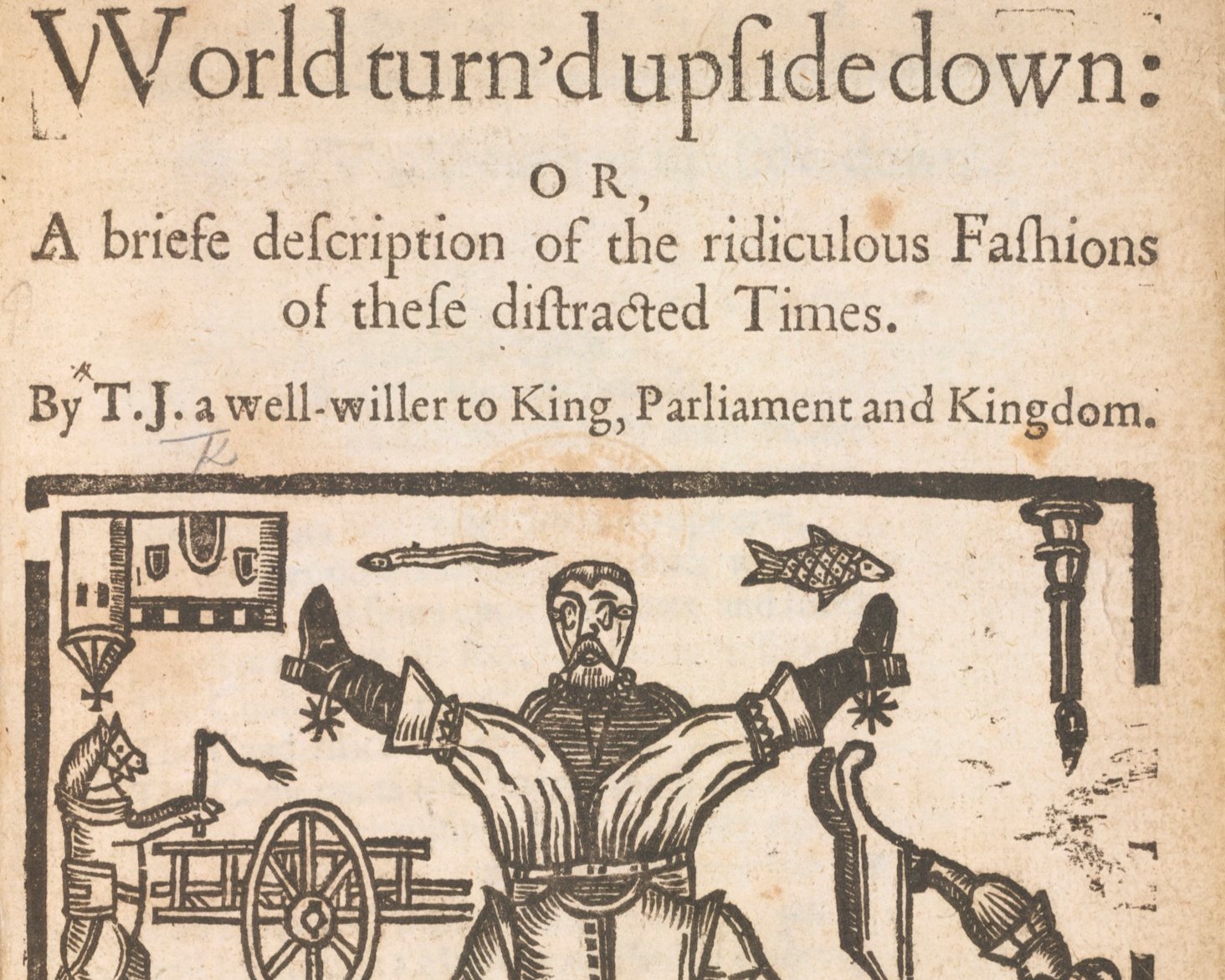

Cover of the English civil-war era pamphlet, T.J., The World turn’d upside down: Or, A briefe description of the ridiculous Fashions of these distracted Times. (London: printed for John Smith, 1647). British Library

Revolutions Before the Revolution

Americans tend to believe that the Revolution took place in 1775 (if you’re from Massachusetts) or 1776 (the rest of the country). But what if the ideas of the Revolution - self-governance and independence, no kings, a government by the people and for the people - preceded 1776 by more than 150 years? What if THE Revolution wasn’t the only revolution at all, but one that followed directly from the fight for rights in 17th century Engalnd and New England?

This fall, join us for our annual lecture series Revolutions Before the Revolution: The 17th Century Fight for Rights, as we delve into the tumultuous, politically contentious past - the time when, as writer T.J. put it, the world turned upside down.

We invite you to explore the radical thought of Levellers, London pamphleteers and MPs who supported the parliamentary forces in the civil wars and whose radicalism is echoed in American Revolutionary era thought.

Meet, too, the hundreds of New England Puritans who returned to England to fight in these civil wars - many at the cost of their lives. Francis J. Bremer looks at the men who crossed the Atlantic in the parliamentary cause and helped to found an English republic.

Nor did the insistence on independence and representation - including the call for no taxation without representation - spring up in the 1770s, as Adrian Chastain Weimer has explained. Where did these revolutionary ideas originate? The 17th century.

“we can’t know who we are until we know our full history, the good and the bad.”

- attendee, A Nation in Balance

Forces loyal to Charles I attack “the Londoners” at Westminster Hall, London, in 1642 - causing “a great rout of ruffinly cavalieires”. Political conflict between the monarchy and his forces, on the one hand, and parliament led to a brutal civil war in the 1640s. New Englanders would join in, many returning to England to take the parliamentary side. After the royalist defeat, Charles I was tried, found guilty of treason, and executed, while Oliver Cromwell became head of state of a republic lasting 11 years. W. Hollar, London, 1642. British Library

TYRANNy vs LIBERTY: POLITICAL CHOICES IN 17TH CENTURY NEW ENGLAND

Imagine a world in which political leaders step down after electoral defeat, where voting is expanded, not restricted, and where the idea of consent is the founding principle of government. Where slavery begins and there is genocidal violence. Was the choice tyranny or liberty - and for whom? Welcome to 17th century New England!

In the election year of 2024, our six-part lecture series, Tyranny vs Liberty: Politics in 17th Century New England, explored the Puritans’ political choices. Would they choose a (relatively) democratic system or rule by with few leaders? Land distribution to the many or the few? Arbitrary rule or a written bill of rights? How would they relate to Indigenous sovereign nations - and how did they justify the tyranny of colonization? Finally - what were the consequences of these decisions?

We had a brilliant line up of historians and Tribal representatives: David D. Hall, Harvard Divinity School; Linda Coombs, Acquinnah Wampanoag and author; Chernoh Sesay Jr., DePaul University; Margaret Newell, Ohio State; Mack Scott, Narragansett and Brown University historian; and Francis J. Bremer, Millersville University professor of history emeritus. Watch their presentations here for a wide-ranging, breathtakingly fascinating view of the political questions of the time and their legacy today. As Oliver Cromwell might say, this is history, warts and all.

WPA artist Earnest Hamlin Baker created this mural, "South County Life in the Days of the Narragansett Planters," which appears in the Wakefield, Rhode Island, post office in ca.1939/40. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

ENSLAVEMENT & RESISTANCE: NEW ENGLAND 1620-1760

Slavery: the very word catapults us into today’s fierce history battles. Did slavery teach enslaved people new skills, as Florida’s new school curriculum asserted? Or is the story both far more brutal and more nuanced, with enslaved people at its center? How should history be taught, remembered, investigated and thought about? What is the truth about our history, and whose truth is it?

Our 2023 fall series, Enslavement & Resistance: New England 1620-1760, took a rigorous, nuanced and accurate look at a part of the past that, in New England, that has been largely denied or minimised.

Nearly 3,000 people registered for our six events, with thousands attending in person, online, and through recordings. Over 90% of you said the presentations were eye-opening and very good. Many of you said what they liked the most was learning something they’d never known, and that they wanted more of the “unvarnished” history that we’re presenting. “You hit it out of the park with this one,” said a member of our audience.

Watch our brilliant presenters: the Rev. Stephanie May, Jared Hardesty, Kyera Singleton, Margaret Newell, Michael Thomas, Rashad Young, Linford Fisher, Alexis Moreis, Cheryll Toney Holley, Loren Spears, Richard Boles, Aabid Allibhai, the Rev. Mary Margaret Earl, and Byron Rushing.

Persistence of place: Tjamel Hamlin II and Derrick Strong, Eastern Pequot tribal members, screen for artifacts with Lan-Huong Nguyen, a former Connecticut College student, at an archaeological site on the Eastern Pequot reservation. The field school’s archaeological findings testify to the commitment to place. Credit: Stephen Silliman

the power of place: land, place and belonging from an indigenous perspective

In our 2022 fall series, The Power of Place, six renowned academics and Native scholars and educators explored the meaning of place – as understood by both Native people and English colonists – and its consequences today.

We saw how, in the mercantile world of 17th century England, land was something to be bought, sold, alienated, acquired, and accumulated - offering power, money, status, and freedom. For New England’s Native people, land was home - so much so that they took their tribal names from the places to which they belonged. Land was not owned in the way that the English understood it; instead, land was family.

Land also lay at the heart of the conflict between English colonists and the Native people of New England: acquiring, exploiting, and controlling it versus developing and maintaining a relationship. Unlike colonists elsewhere, the Puritans were not motivated by money - many left more comfortable, wealthier lives at home in England. But the underlying difference in ideas of land and ownership, what was valued and what was “wasteland,” and what a title deed might mean, led to a cumulative process in which Native people were virtually disenfranchised and stripped of their land.

Understanding the power of place from an Indigenous point of view illuminates the key turning points in New England’s early history, including its violent wars. As our presenters showed us, there is also the story of harmony, respect and honor for the land and its people.

Whose common good? The Puritans established their Common in Boston in the 1630s - on the land of the Massachuset tribe.

the common good: Whose good, whose common?

Would the Puritans have worn covid masks?

Across the world, but especially in the United States, we’re struggling with the question of community vs the individual. How do we balance the rights of the individual against what’s best for everyone? Can we have shared values? And is the question of the individual vs the collective truly a conflict? For the Puritans, keenly aware of individual liberties, fulfillment also came from the common good – the building of a community “knitt together,” as John Winthrop put it, in work, prayer, sickness, and health. The wellbeing of one meant the flourishing of all.

Our 2021 fall lecture series, The Common Good, explored this founding principle of Massachusetts’ Puritans and how they created a society knit together, even as the faultlines began to appear. The cost of that tightly knit community were those who were excluded: heretics, the Black people viewed as rightly enslaved, the Native peoples regarded as enemies, and the English rebels who were banished. We also asked: what would New England society look like today if the colonists had respected a Native way of living?

Our six fascinating presentations can be viewed here.

“I LOVED HOW THE SPEAKER TIED THE PAST TO TODAY, AND MOVED BEYOND STEREOTYPES.”

- attendee, Tyranny vs. Liberty

PLUNGE INTO THE PAST WITH OUR FALL LECTURE SERIES

Are you ready for a fascinating crash-course in New England history? We bring you the best every fall with our annual lecture series.

For two decades we’ve marked Boston’s founding in September, 1630, with lectures on new topics each year. We’ve delved into death and disease (click here for our 17th century medical glossary.) We’ve rescued the Puritans from their sex-hating reputation. With members of the Massachuset tribe, we’ve explored Boston before European settlement and colonization’s brutal consequences.

Join scholars and other experts in exploring the meaning of history. We think you’ll enjoy it. As one audience member told us, “What did I like? Everything. Just everything.”

17th century engraving depicting the figure of “Fancie,” or imagination, by an unknown artist. Image: Wellcome Collection

Past lecture series

2025 Tyranny vs Liberty: Political Choices in 17th Century New England

2024 Enslavement & Resistance in 17th Century New England

2023 The Common Good: Whose Good, Whose Common?

2022 The Power of Place: Indigenous Perspectives and Experiences in 17th Century New england

2021 The Common Good: Whose Good, Whose Common?

2020 Recognizing the 400th Year: How We Got Here

2019 Puritan Primetime: Politics, Faith, Children and Money in 17th Century Boston

2018 From Theology to Commerce: The Evolution of Massachusetts Bay Colony in the Puritan Era

2017 Medicine and Mortality in 17th Century Boston

2016 Passionate Puritans: Marriage, Love, and Sex in 17th Century Massachusetts

2015 Food and Drink in Early Boston

2014 Survival: Boston 1630

2013 Crime and Punishment in Early Massachusetts

2012 Stirring the Pot: Women in Early Massachusetts

2011 Built in the Massachusetts Bay Colony: 17th Century Architecture Adapted to the New World

2010 Education: Enduring Legacies from Massachusetts

2009 Breaking Away: Evolution of Governance in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

2008 The Story of the Massachuseuk: In the Time Before Now

2007 Treasures of the Mass Bay Colony

2006 Boston’s Cultural Continuities and Changes Since 1630

2005 Shared Legacies: The Founding Generations Tell Their Stories: Massachusetts Bay Colony, 1630-1710

2004 Boston on Display: The Founding Generation

2003 The Environment

2002 Learning Today from the Lessons of the Past

2001 First Boston Charter Day following Governor Jane Swift’s proclaiming September 7 as Boston Charter Day