read

BOOK REVIEWS

TRY OUR BOOK OF THE MONTH!

book of the month: January/February 2026

Edmund S. Morgan, The Puritan Family: Religion and Domestic Relations in Seventeenth-Century New England, originally published 1944, revised edition 1966.

Reviewed by David Achenbach

Edmund Morgan was an authority on early American history at Yale University. This book, the first of his distinguished career, derived from his 1942 PhD thesis at Harvard. Originally published as a series of articles by the Boston Public Library, Puritan Family was revised and enlarged and published as a book by Harper & Row in 1966. It has not been out of print since.

Morgan wrote two additional books on the Puritans: a biography of John Winthrop, The Puritan Dilemma (1958) and Visible Saints: The History of a Puritan Idea (1963). With the historians Samuel Eliot Morrison and Perry Miller, Morgan is credited with the 20th century rehabilitation of the 19th century image of the Puritans as somber killjoys.[1] Determined to understand the Puritans on their own terms, Morgan said that he learned from Miller to appreciate, “the intellectual rigor and elegance of [the Puritan] system of ideas that made sense of human life in a way no longer palatable to most of us.”[2]

In The Puritan Family, Morgan is at pains to explore the impact of Puritan religious beliefs and practices on domestic relations. A model Puritan practiced religion with an intensity alien to most of us today. The abundant sermons of ministers and the diaries of lay Puritans attest to the agonies attending the uncertainty of salvation - which was always God’s free gift and beyond any power of person to influence. Puritans sought to know and obey God’s laws not to earn salvation - the dreaded “covenant of works” - but rather because they believed that good works followed salvation as “the natural and necisary Companions of…faith.”[3]

In successive chapters, Morgan describes how Puritans applied scriptural teachings to relationships between husbands and wives, parents and children, and masters and servants. This included servants of all descriptions, whether hired, indentured or enslaved; all were being considered a part of their master’s family.

For the Puritans, all aspects of family life held a religious dimension, sometimes in ways that we now find jarring. Children were educated to read, not for the sake of accumulating knowledge, but so they could read the Bible. As Morgan put it,

The Puritans sought knowledge…not simply as a polite accomplishment nor as means of advancing material welfare, but because salvation was impossible without it. [They] rested their whole system upon the belief that “[e]very Grace enters in to the Soul through the Understanding.” In order to be saved, people had to understand the doctrines of Christianity, and since children were born without understanding, they had to be taught.[4]

Similarly, relations between servants and masters were thought to be governed by religious strictures. According to Morgan, for the Puritans

[i]t made no difference whether the master was kind or unkind, harsh or lenient; his servants must obey every command, “because the primary ground of this duty is not the merit of the Master, but the ordinance of God.” “[W]hen your Master or Mistress bids you do this or that, Christ bids you do it, because he bids you obey them.[5]

A criticism of the book might be that Morgan concentrates his attention on solely Puritan families, rather than 17th and 18th century New England families more broadly. I would applaud his honesty: he never claims to apply his findings beyond the Puritan fold. Later historians have written excellent and insightful works that consider additional aspects of families, and other types of families, in this period, using different tools and varied perspectives. For example, Gloria Main, in Peoples of a Spacious Land: Families and Cultures in Colonial New England (2001), compared English and Native families and incorporated insights from psychology and anthropology. Mary Beth Norton’s Founding Mothers & Fathers: Gendered Power and the Forming of American Society (1997), considers contemporary political theory and takes a regional Atlantic history perspective, contrasting domestic relations in early modern England, New England, and Virginia.

I believe that Morgan’s The Puritan Family remains canonical on its own ground - Puritan religious thought and practice as applied to family relations. Arguably never superseded, it remains as invaluable today as when it was first written.

David Achenbach earned degrees in history from the University of Birmingham, England, and in law at Suffolk University. He worked in human resources, mostly for colleges and universities in Massachusetts and Washington DC. Now retired, he is a tour guide for Historic New England and the Nichols House Museum, in addition to running, gardening, and reading as much history as he can get a hold of!

[1] Francis J. Bremer, Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction (2009), p. 107.

[2] Edmund S. Morgan, The Genuine Article: A Historian Looks at Early America (2003), p. ix.

[3] Puritan Family, p. 4, quoting Boston Sermons, 1671-79, August 5, 1677.

[4] Puritan Family, pp. 89-90, quoting Cotton Mather, Cares about the Nurseries (1702).

[5] Puritan Family p. 112-13, quoting William Ames, Conscience, with the Power and Cases Thereof (1643) and Benjamin Wadsworth, The Well Ordered Family (1712).

Kristin Olbertson, The Dreadful Word: Speech Crime and Polite Gentlemen in Massachusetts, 1690-1776 (Cambridge University Press, 2022), 258pp.

Reviewed by Stuart Christie

Why not just let the vulgar be vulgar?

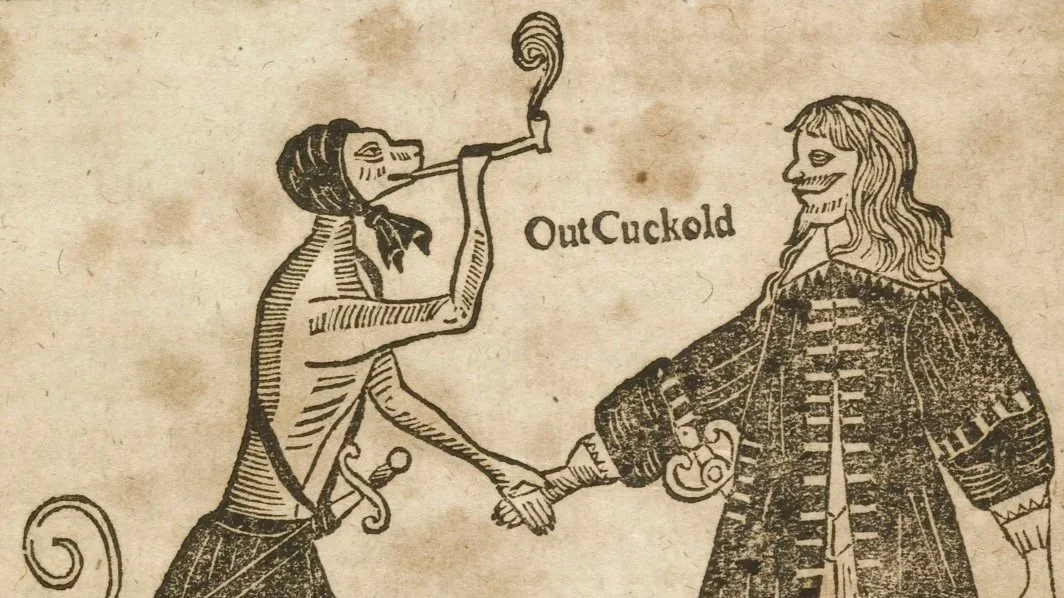

With this question Kristin Olbertson opens her study of speech crimes in Massachusetts between the end of the 17th century and the outbreak of the American Revolution. Over the next 258 pages she provides a well-researched and highly entertaining answer. At the heart of the answer are the evolving rules governing speech, as the colony moved from a Puritan-based legal system to one driven largely by secular standards.

Supporting Olbertson’s argument are thousands of court cases from Massachusetts and part of Maine from 1690 to 1776. Interspersed with her examination of these cases are the observations of colonial and British luminaries such as Cotton Mather, John Adams, Jonathan Swift, Daniel DeFoe, Richard Sheridan, and William Blackstone. The result is a narrative alive with the language, reasoning, prejudices, and perceptions of the times.

What the Puritans and then later colonial officials pursued was a campaign to prevent society from falling down the slippery slope of “idleness, debauchery, and violence.” To this end, they prosecuted blasphemy, profanity, and other verbal offenses. Profanity was, of course, a gateway offense to “Swearing, Cursing, Profaneness, Drunkenness, Whoredom, Theft, Robbery, Murder, and the Gallows….”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, while the legal system shifted from being one based on religious principles to one of secular morality, a consistent factor was the focus on class – the better sorts versus the meaner.

As Olbertson relates, the courts followed social hierarchy in dealing with “insensitive language,” broken down in the following rank order:

The elites, who set the rules for themselves, versus the “others.” Their basis for setting those rules was an inherent sense of what was right that “even an act of Parliament cannot alter.” They were rarely tried and even more rarely fined. When fined, it was likely to be for a token amount.

Workingmen lacked the privacy available to wealthy people, and were therefore more likely to be overheard and reported to the authorities. As the meaner sort, they were viewed as more likely to use “insensible” language. Consequently, theirs were the majority of the cases, and their fines tended to be greater than those of the elites.

Not surprisingly after months at sea in a “men only” environment followed by a visit to the nearest grog shop, sailors were prime suspects for the use of hostile and uncivil language – as were their captains. Like other workmen, their fines were greater than those of the elites, and most presented to the court were found guilty.

The number of court cases involving Black and Indigenous people far exceeded their relative numbers in society. In most cases, they were found guilty and harshly penalized. The penalty for profane speech was often a fine, but since most had little or no money, they could be whipped instead.

Women were more likely to be present in court for running inns where swearing took place, than for actually swearing themselves. Obertson attributes the relatively small percentage of cases against women as a reflection of their declining role in colonial life in the 18th century from that in the 17thcentury, and despite their perceived less “governed tongues.”

In discussing the credibility of someone accused of vulgar speech, Olbertson highlights the great conundrum of 18th century acceptable speech. In order to be polite, the speaker was virtually forced to lie. The lie may have been a simple “stretching the truth” or telling a “white lie,” but it was still a lie. Fortunately, for the elite who were most directly governed by the rules of etiquette, the rules were made by their peers. As a result, the laws were written so that only “big” lies, i.e., those impacting public order, or lies made under oath (perjury), were crimes.

Sexism, racism and xenophobia fundamentally shaped the court’s views on veracity. Women were viewed as frequent liars, the French had “two tongues,” and Black people were “nowhere white, but in the Mouth” (suggesting that their words and actions were in opposition).

In her closing chapter, Olbertson discusses how the focus on the lack of politeness in speech crimes shifted to accusations of sedition with the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. In the 19th century, the focus shifted again, to one of respectability with the rise of the middle class. Olbertson ignores the 20th century entirely but does briefly touch on two attributes of the 21st century, the internet and “fake news.”

The Dreadful Word is thoroughly annotated with numerous footnotes. Yet some of Olbertson’s conclusions, based on a small number of cases, are questionable. In particular, what’s doubtful is her claim that the relatively few cases involving elites was evidence that elite members of society were less prone to being charged. In fact, they were far fewer in number as a share of the population; it therefore stands to reason that fewer would be tried.

Another minor issue in this generally fascinating and readable book was the occasional use of cringe-worthy, anti-drug campaign slogans to make the cases “relevant.”

Yet her primary argument – that vulgarity defined class and merited tangible punishment to define the obverse, gentlemen – stands up. As she writes, “The vulgar could not simply be allowed to be vulgar; they were needed, in the dock, in the stocks, and at the whipping post, to define what a sensible and civil speaking gentleman was not.” Or, in the words of Gelett Burgess, “I’d rather see than be one.”

*

Stuart Christie has been a docent at the Fairbanks House Museum in Dedham for 11 years. He has served on the boards of the Dedham Museum and Archive (formerly the Dedham Historical Society), as well as the Partnership of Historic Bostons. He is a member of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts and the Olde Colony Civil War Roundtable.

Stuart transcribed, compiled, and produced the book, My Dear Mother: Civil War Letters to Dedham from the Lathrop Brothers. He is currently working on a book based on his experiences in the Vietnam War.

Andrew Lipman, Squanto: A Native Odyssey (Yale University Press, 2024), 259pp.

Reviewed by Stephen Hahn

Andrew Lipman’s Squanto: A Native Odyssey is both the biography of a legendary figure in the history of early English settlement in what came to be called Plymouth Plantation (Patuxet) and something more expansive. In its broader scope, the story of Squanto, “the man from Patuxet,” provides a lens into the history and culture of the Wampanoag people and English settlers in the first quarter of the 17th century.

For several generations in the early 20th century, the image of Squanto as a sachem interacting with English settlers at the Puritans’ “first Thanksgiving” was mediated popularly by copies of nostalgic paintings from the Colonial Revival era, like the one to the left by by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris, or by Jennie Augustus Brownscombe (both 1914) - on calendars, lithographs, and transfers to textiles and dinnerware, creating a scene of concord. None was historically accurate. Later generations were entertained by comics, cartoons, fictional films, and purported documentaries of uneven factual accuracy and narrative consistency - all of which Lipman examines in his final chapter on Squanto-the-legend’s “afterlives.”

Lipman’s narrative proper, however, begins with an ethnographic reconstruction of Squanto’s likely experience as a young man in the culture of the southern Dawnlands. It proceeds to the story of Squanto’s abduction by European traders and his arrival in the slave-trading port of Malaga, Spain, where he and others abducted with him escape the fate of African slaves due to the intercession of a Jesuit priest who had caused Catholic Spain to ban trade in Indigenous people, originating in Nueva Mundo. Following his liberation, Squanto journeyed through England, Newfoundland, Jamestown, and Plymouth, England, returning home after five years to discover his people had been decimated by the Great Dying. Squanto establishes himself as a native leader in negotiations that involve Ousamequin (also called “the Massasoit”) and the legendary Samoset (from more northern Dawnlands). The story ends with Squanto’s death as an enigmatic but potentially tragic figure, who had been instrumental to the survival of the English, but died as a result of what might have been poisoning or adventitious disease.

Lipman’s narrative, especially the speculative ethnographic reconstruction of the world into which Squanto is born, is informed by recent scholarship on early 17th century Massachusetts, and by his craft in weaving together strands of the story to include the differing perspectives of Wampanoag natives and the English settlers. His work continues the project of other contemporary historians, widening the view of early Puritan New England/Eastern Woodlands to encompass the greater Atlantic world of exploration, exploitation, and enterprise.

Thoroughly researched and well-documented, the book is accessible to general readers and scholars, and may also suit advanced high school students. The use of the comparative framing device of the Homeric Odyssey amplifies the pathos of Squanto’s alienation from and return to his homeland, and the approach of a generalized subjunctive voice (“he would have…”) in the treatment of Squanto’s youth helps readers imagine a youthful version of a Squanto not in any specific historical record. Yet the use of literary devices may lead to scholarly scrutiny about the strictness of historical method.

Overall, there are three major contributions that Lipman’s work makes in the context of existing scholarship on Squanto: (1) the expansion of the trans-Atlantic dimension of his story, based on historical evidence, to include the years he was away from his homeland and offer an explanation his acquisition of fluency in English, which enables him to become a translator, negotiator, and perhaps more covert agent in the story; (2) the thesis of a seasonal Patuxet native village positioned across the falls from the Plimoth colony under the leadership of Squanto during the critical years 1620-22, as a point of native surveillance and intercourse with the English, whose polity is more mixed than usually supposed: and (3) an emphasis on the critical role that Wampanoag practices of naming of places and persons, and on the cultural significance of filiation linking place and person, in shaping communication and misunderstandings with the English during these years.

Finally, the chapters of this book comprise relatively short but rich narrative essays. They reward rereading not just to capture a fact or reference one may have forgotten but for the actual quality of an evolving story they convey. Whatever one’s dominant interest in the threads of the story, one is likely to find more than one intriguingly new perspective on a tale many times more than twice told.

*

Stephen Hahn is a professor of English, emeritus, William Paterson University. A native of Essex county, Massachusetts, he currently lives in Falmouth, Maine. He currently teaches at the Maine Coastal Senior College.

Elaine G. Breslau, Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem: Devilish Indians and Puritan Fantasies (New York University Press, 1996).

Reviewed by Evana Rose Tamayo

When the accused Salem witch Sarah Good stood trial, she failed to discredit Tituba’s testimony against her. It was an unprecedented moment: the court . accepted an Arawak slave’s testimony against a white Puritan. In highlighting this rare event, Elaine Breslaw’s Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem affirms the central figure of her book as not only a victim, but a woman of agency.

Little is known of Tituba, in part because of the paucity of Puritan records. In a quest to reconstruct the enslaved woman’s life, Breslaw traveled to Barbados to consult colonial records as well as local historians and scholars. There, she uncovered a “Tattuba negro” listed in a plantation inventory, and from that record, traces later Barbadian references, providing a wealth of historical context to Tituba’s story. Breslaw acknowledges that her case is circumstantial. Yet, writing a historical book influenced by anthropology, geography, and cultural history, Breslaw provides access to a cultural context that might otherwise be lost to history.

Who was Tituba? Originally an Amerindian in Barbados, where Indigenous people were considered dangerous, she was raised among African slaves. With the African population numbers outpacing white, her classification as a “negro” may also have made her suspect. On the other hand, as Breslau argues, her creolized identity might have furthered her value as a servant, explaining her sale to the Rev. Samuel Parris.

Yet this complex identity made Tituba as vulnerable in Salem as in Barbados. Puritan Mary Sibley, involved in the witch cake incident with Tituba, received a mild punishment; Parris gained deniability. Tituba, by contrast, was later accused of witchcraft and imprisoned.

Recovering the lives of the marginalized is inherently difficult, and Breslaw’s unconventional approach must be read with that in mind. At times she risks overstating causation where evidence is thin.

Nonetheless, Tituba, Reluctant Witch of Salem is a compelling and innovative attempt to recover the life of a woman nearly lost to myth. Breslaw contributes significantly to our understanding Tituba and her fate. Even if they question her conclusions, readers will find much of value.

book of the month: august

Malcolm Gaskill, The Ruin of All Witches: Life and Death in the New World (London: Allen Lane, 2021).

Reviewed by Sarah Stewart

In the frontier town of Springfield in 1651, rumours began to spread. After a spate of mysterious illnesses, children perishing overnight, crops failing – something, someone had to be found responsible. First a wife, Mary Parsons, accused her husband Hugh Parsons of witchcraft. Then neighbours, already disliking the belligerent brick maker, pointed the finger. Both husband and wife were charged with witchcraft. Mary died in prison; Hugh survived his trial.

Malcolm Gaskill’s captivating tale of the disintegration of a marriage and the descent of a community into fear, envy, and darkness is both quotidian and heartbreaking. In his beautifully crafted recreation of 1651 Springfield, there is no accusation too petty, no fear that was not magnified, no resentment that could not blossom into malevolence. It is wrenching to read the small but steady steps taken towards tragedy by a community always aware of demonic forces and hearing of witches far and near. The Ruin of All Witches is a compelling, important introduction to the claustrophobic, spiteful world of accuser and accused in New England witchcraft.

What makes this book stand out, however, is not just this intimate portrait. Gaskill rejects the longstanding idea of witchcraft as a form of hysteria in favor of a more rigorous analysis. “[W]itchcraft was not some wild superstition,” he writes, “but a serious expression of disorder embedded in politics, religion and law.” In Springfield, the larger forces of political and theological disorder pressed down on mental illness, envy, hunger and scarcity, with tragic results.

Read more

There’s a vast literature of exciting work on early New England. The lists we’ve compiled only begin to scratch the surface. For fear of overwhelming readers, we’ve listed just some of our favourites – there are many more on our overflowing bookshelves.

If you’ve got a book to recommend, let us know! Email phbostons@gmail.com.

General

Bailyn, Bernard. The Barbarous Years: The Peopling of British North America: The Conflict of Civilizations, 1600-1675. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

Bragdon, Kathleen J. Native People of Southern New England, 1500-1650. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996.

——————————-. Native People of Southern New England, 1650-1775. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2020.

Bremer, Francis J. One Small Candle: The Plymouth Puritans and the Beginning of English New England. New York: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Grandjean, Katherine. American Passage: The Communications Frontier in Early New England. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Hall, David D. The Puritans: A Transatlantic History. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Philbrick, Nathaniel. Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War. New York: Penguin, 2006.

Silverman, David J. This Land is Their Land: The Wampanoag Indians, Plymouth Colony, and the Troubled History of Thanksgiving. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Everyday life

Hall, David D. Worlds of Wonder, Days of Judgment: Popular Religious Belief in Early New England. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Deetz, James and Patricia Scott Deetz. The Times of Their Lives: Life, Love, and Death in Plymouth County. New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

Morgan, Edmund S. The Puritan Family: Religion and Domestic Relations in Seventeenth-Century New England. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

Puritanism

Bremer, Francis J. First Founders: American Puritans and Puritanism in an Atlantic World. Lebanon, NH: University of New Hampshire Press, 2012.

Bremer, Francis J. Puritanism: A Very Short History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Bremer, Francis J. John Winthrop: America’s Forgotten Founding Father. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Cooper, James F. Tenacious of Their Liberties: The Congregationalists in Colonial America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Hall, David D. A Reforming People: Puritanism and the Transformation of Public Life in New England. New York, Knopf, 2011.

Morgan, Edmund S. The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop. New York: Pearson, 2007.

Rogers, Daniel. As a City on a Hill: The Story of America’s Most Famous Lay Sermon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2018.

Rogers-Stokes, Lori. Records of Trial from Thomas Shepard's Church in Cambridge, 1638-1649: Heroic Souls. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Women

LaPlante, Eve. American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the Puritans. New York: Harper Collins, 2004.

Ulrich, Laurel Thatcher. Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England 1650 – 1750. New York: Vintage, 1980/1991.

black new england

Greene, Lorenzo, The Negro in Colonial New England. New York: Columbia University Press, 1942.

Handouts for Recovering Black History: A Workshop, presented by Michelle Stahl, Monadnock Center for History and Culture, and Jennifer Carroll, Historical Society of Cheshire County, April 17, 2024, for local historians identifying the Black community in early New England:

Town History Research and Search Terms

witchcraft

Baker, Emerson W. A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Baker, Emerson W. The Devil of Great Island: Witchcraft and Conflict in Early New England. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007.

Behringer, Wolfgang. Witches and Witch-Hunts: A Global History. Wiley, 2004.

Gagnon, Daniel A. A Salem Witch: The Trial, Execution and Exoneration of Rebecca Nurse. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2023.

Gaskill, Malcolm. The Ruin of All Witches: Life and Death in the New World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2022.

Gaskill, Malcolm. Witchfinders: A Seventeenth-Century English Tragedy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Hite, Richard. In the Shadow of Salem: The Andover Witch Hunt of 1692. Westholme, 2018.

Moyer, Paul B. Detestable and Wicked Arts: New England and Witchcraft in the Early Modern Atlantic World. Cornell University Press, 2020.

Norton, Mary Beth. In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002.

Elizabeth Reis. Damned Women: Sinners and Witches in Puritan New England. Cornell University Press, 1997.

Roach, Marilynne. The Salem Witch Trials: A Day by Day Chronology of a Community under Siege. New York: Cooper Square Press, 2002.

Roach, Marilynne. Six Women of Salem: The Untold Story of the Accused and Their Accusers in the Salem Witch Trials. Boston: Da Capo Press, 2013.

Rosenthal, Bernard et al, eds. Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Ross III, Richard S. Before Salem: Witch Hunting in the Connecticut River Valley, 1647-1663. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2017.

WEBSITES

Salem Witch Trials: Documentary Archive and Transcription Project https://salem.lib.virginia.edu

17th Century New England, with Special Emphasis on the Essex County Witch Hunt of 1692 http://www.17thc.us/

Cornell University Witchcraft Collection https://rmc.library.cornell.edu/witchcraftcoll/

Salem’s Trials: Lessons and Legacies of 1692. A Symposium held at Salem State University on June 10, 2017, to commemorate the 325th anniversary of the witch trials. Available at: https://www.c-span.org/organization/salem-state-university/45222/

WATCH AND LISTEN

"The Salem Witch Trials: Interpreting History and Finding Relevance" a presentation by Dan Lipcan and Paula Richter, curators at the Peabody Essex Museum, for PHB. Watch it here.

Unobscured with Aaron Mahnke, Season One: The Salem Witch Trials https://www.grimandmild.com/unobscured

The Thing About Witch Hunts witchhuntshow.com

The Thing About Salem aboutsalem.com

RADICALISM AND RESISTANCE IN THE ENGLISH RESISTANCE: A READING LIST FROM RACHEL FOXLEY, UNIVERSITY OF READING

A nice accessible survey of political ideas before the English Revolution is Johann Sommerville, Royalists and Patriots: Politics and Ideology in England, 1603-1640 (second edition) (1999).

On the English Revolution, there are plenty of good books! A good collection of shorter chapters on different themes is the Oxford Handbook of the English Revolution (2015), edited by Michael Braddick.

On the Levellers:

I’ve written a very short chapter introducing the Levellers in Laura Lunger Knoppers (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Literature and the English Revolution (Oxford, 2012).

Longer works on the Levellers:

Gary De Krey, Following the Levellers (London, 2017), volumes 1 and 2. Volume 1 looks at the Leveller movement itself; volume 2 traces the future lives of Leveller followers after the collapse of the movement.

John Rees, The Leveller Revolution: Radical political organisation in England, 1640-1650 (London, 2017) is a good accessible telling and analysis of the movement.

Pauline Gregg, Free-born John : a biography of John Lilburne (1961) is still readable and useful. A newer biography is by Michael Braddick, The Common Freedom of the People: John Lilburne and the English Revolution (2018) – this emphasizes Lilburne’s engagement with ideas of law.

More academic works are my own book, Rachel Foxley, The Levellers: Radical political thought in the English Revolution (Manchester, 2013); and the brilliant book by David Como Radical Parliamentarians and the English Civil War (Oxford, 2018), which doesn’t get as far as the height of the Leveller movement, but uncovers the roots of Leveller and radical ideas earlier in the revolution in great (and very illuminating) detail.

The article on the afterlife of the Leveller movement (or Lilburne specifically) is Edward Vallance, ‘Reborn John: The Eighteenth-century afterlife of John Lilburne’, History workshop journal , 10/2012, Volume 74, Issue 74

On the republicans:

Blair Worden, Literature and Politics in Cromwellian England: John Milton, Andrew Marvell, Marchamont Nedham (Oxford, 2007) traces the careers of two of the republicans I briefly mentioned, placing them in the detailed context of politics in the 1650s.

Rachel Hammersley, James Harrington: An Intellectual Biography (Oxford, 2019) is the most authoritative work on all aspects of Harrington’s work and political thinking. Her book Republicanism: An Introduction (Cambridge, 2020), offers a very accessible introduction to republican ideas across periods, with a chapter on the English Revolution and further chapters on eighteenth-century republicanism and the American and French Revolutions – this is a really clearly written book which I would highly recommend.

We would add two more books to Rachel Foxley’s list:

Philip Baker, ed., and Geoffrey Robertson, intro., The Levellers: The Putney Debates (London: Verso Books, 2007).

Andrew Sharp, ed., The English Levellers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), which includes 14 Leveller pamphlets and broadsheets.

Slavery

Secondary sources

Allibhai, Aabid, “Race & Slavery at the First Church in Roxbury: The Colonial Period, 1631-1775,” Unitarian Universalist Church, February 3, 2023.

Boles, Richard, Dividing the Faith: The Rise of Segregated Churches in the Early American North. New York: New York University Press, 2020.

DasSarma, Anjali, and Linford D. Fisher, “The Persistence of Indigenous Unfreedom in Early American Newspaper Advertisements, 1704-1804,” Slavery & Abolition, March 30, 2023, 1-25.

Fisher, Linford D., “‘Why Shall Wee Have Peace to Bee Made Slaves’: Indian Surrenderers During and After King Philip’s War,” Ethnohistory 64, no.1 (January 1, 2027), 91-114.

Gonzalez, Eduardo, “Of One Blood? Cotton Mather’s Christian Slavery”, historicbostons.org

Hardesty, Jared Ross, Black Lives, Native Lives, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019.

Hardesty, Jared Ross, Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston. New York: New York University, 2016.

Harvard University, “Responsibility and Repair: Legacies of Indigenous Enslavement, Indenture, and Colonization at Harvard and Beyond,” conference, November 2 and 3, 2023.

Harvard University, “Report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery.” Cambridge, MA: Harvard University, 2022.

Manegold, C.S. Ten Hills Farm: The Forgotten History of Slavery in the North. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010.

Maskiell, Nicole Safford, “‘Here Lyes the Body of Cicely Negro’: Enslaved Women in Colonial Cambridge and the Making of New England History,” New England Quarterly, vol. XCV, no. 2, June 2022.

Newell, Margaret Ellen, “Our Hidden History: Roger Williams and Slavery’s Origins,” Providence Journal and Bulletin, August 29, 2020.

Newell, Margaret Ellen, “The Changing Nature of Indian Slavery in New England, 1670-1720,” in Colin G. Calloway and Neal Salisbury, eds., Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience. Boston: The Colonial Society of Massachusetts, 2003, 106-136.

Newell, Margaret Ellen, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2015.

Sesay Jr., Chernoh M., “The Revolutionary Black Roots of Slavery’s Abolition in Massachusetts,” in New England Quarterly, vol. LXXXVII, no. 1, March 2014.

Tucker, Wayne, Eleven Names Project: Recovering Enslaved People of Massachusetts, substack

Warren, Wendy. New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America. New York: Liveright/W.W. Norton, 2018.

Primary sources

Jonathan Edwards’s church records from Northampton, Mass., Congregational Library & Archives.

“Flora's confession and testimony, 1749 July 23” from the Second Church of Ipswich, Mass., Congregational Library & Archives.

Mather, Cotton, A Good Master Well Served. A Brief Discourse on the Necessary Properties & Practices of a Good Servant in Every-Kind of Servitude. Boston: B. Green and J. Allen, 1696.

Mather, Cotton, The Negro Christianized. An Essay to Excite and Assist that Good Work, The Instruction of Negro-Servants in Christianity. Boston: B. Green, 1706.

Mather, Cotton, “Rules for the Society of Negroes,” broadsheet, 1693.

Sewell, Samuel, The Selling of Joseph: A Memorial. Boston: printed by Bartholomew Green and John Allen, 1700.

Stolen Relations: Recovering Stories of Indigenous Enslavement in the Americas.

war for the dawnland/King Philip’s War

Brooks, Lisa. Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018.

DeLucia, Christine M. Memory Lands: King Philip’s War and the Place of Violence in the Northeast. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019.

Lepore, Jill. The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity. New York: Vintage, 1999.

Mandell, Daniel R. King Philip’s War: Colonial Expansion, Native Resistance, and the End of Indian Sovereignty. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

March, Kevin A. “‘The Violences of Place and Pen’: Identities and Language in the Twentieth-Century Historiography of King Philip’s War.” Madison Historical Review, Volume 17, Article 3, 2020.

McBride, Kevin et al. “The 1676 Battle of Nipsachuck: Identification and Evaluation,” technical report, National Park Service, American Battlefield Protection Program. April 12, 2013.

Schultz, Eric B. and Michael J. Tougias. King Philip’s War: The History and Legacy of America’s Forgotten Conflict. New York: Countryman Press, 2000.

Native people of the Eastern Woodlands

William Apess. On Our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot, ed. Barry O’Connell. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992.

Calloway, Colin G. After King Philip’s War: Presence and Persistence in Indian New England. Hanover: Dartmouth College Press, 1997.

Coombs, Linda. Colonization and the Wampanoag Story. New York: Crown Books, 2023.

Demos, John. The Unredeemed Captive: A Family Story from Early America. New York: Penguin, 1995.

Lopenzina, Drew, Through an Indian’s Looking-Glass: A Cultural Biography of William Apess, Pequot. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2017.

Lopenzina, Drew, Red Ink: Native Americans Picking Up the Pen in the Colonial Period. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2012.

Mandell, Daniel R. Tribe, Race, History: Native Americans in Southern New England, 1780-1880. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010.

National Park Service, “Native Americans and the Boston Harbor Islands.”

O’Brien, Jean M. Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Sakonnet History Project and Little Compton Historical Society. Reconnections: Essays and Artwork by Wampanoag and Narragansett Knowledge Keepers. Little Compton Historical Society, Rhode Island, 2025.

Soliz, Chester P. The Historical Footprints of the Mashpee Wampanoag: Appeal to the Great Spirit. Sarasota, Florida: Bardolf & Company, 2001.

Strobel, Christoph. Native Americans of New England. Praeger, 2020.

Waabu O’Brien, Frank, Understanding Indian Place Names in Southern New England. Boulder: Bauu Press, 2010.

Warren, James. God, War and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians against the Puritans of New England. New York: Scribner Publishing, 2018.

Williams, Roger. A Key Into the Language of America, ed. Dawn Dove, Sandra Robinson, Loren Spears, Dorothy Herman Papp, Kathleen Bragdon. The Tomaquag Museum Edition. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, 2019.

The tribes of the Eastern Woodlands also provide important histories of their people, including museums. This is not a complete list.

Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center

Mashantucket (Western) Pequot Tribal Nation

Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag

Nulhegan Abenaki Tribe at Nulhegan-Memhremagog

Wampanoag Tribe of Chappaquidick

Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah)