a path not taken

The idea is pervasive that early New England’s people were neatly divided, living almost entirely separate lives, African enslaved people, Indigenous people, and English Puritans each in their own, self-contained worlds. Lori Rogers-Stokes’ groundbreaking new book, Gathered Into a Church: Indigenous-English Congregationalism in Woodland New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2025), fundamentally challenges this idea. She looks instead at how people really lived, in mingled communities, in one of the most important areas of New England life: their faith. And at how Indigenous people, fully part of Congregationalism, helped to shape that faith.

This blog is an excerpt from the introduction to Gathered Into a Church: Indigenous-English Congregationalism in Woodland New England. PHB readers can purchase the book with a 20% discount from the publisher, using the code UMASS20.

Congregationalism, born in Woodland New England in the 17th century, was unique, defined by its origin and long practice in the region. It was, moreover, a crucial identity for Indigenous and English people alike for more than two centuries. Its concept of the church body and church kinship was unparalleled in other Christian denominations.

As the name suggests, Congregationalism was based on the primacy and autonomy of the individual congregation. There was no church hierarchy established by and living within the civil government – no archbishops, bishops, vicars, or rectors. There was no head of the church because there was no such thing as the church in the sense of an organization made up of hundreds or thousands of individual parishes governed by bishops, who reported to archbishops, who conferred with the monarch and carried out their orders. Congregationalism located all decision-making within each individual group of believers, or congregation. No outside authority dictated their actions or made policy for them, and individual congregations were not incorporated into or governed by any larger organization or institution.

Congregationalism is not as well understood today as it might be, in part because many of the church record books that every congregation depended on to represent its eternal life, its actions, its people, and its way, have been lost. This sometimes happened through carelessness: as people’s understanding of their importance faded, the books might be loaded into cardboard boxes and stacked on wet basement floors or stored behind Christmas ornaments in church closets. Loss might also be the result of reverent but misplaced attempts to preserve church history, when record books were hidden in safes whose combinations were subsequently forgotten or stored in ministers’ homes and then accidentally auctioned off as part of their posthumous estates. Records were also frequently lost in the many catastrophic fires that consumed wooden meetinghouses in Woodland New England and continue to pose a threat to those still standing.

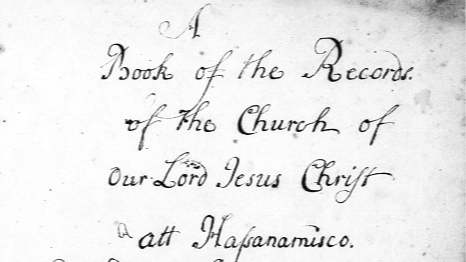

On February 4, 1733/34, five members of a Nipmuc family, the Abrahams - Deborah, Andrew, John, Jonas and Elizabeth - were baptised in the Hassanamisco congregation, as recorded in the Hassanamisco church book, 1731-1774, in the Grafton, Massachusetts, Evangelical Church records, RG 4921, Congregational Library & Archives, Boston

The disappearance of Congregational church records from the historical archive has been devastating to our understanding of Woodland New England in the 17th and 18th centuries. We know this because those that are available have made a massive contribution to demographic records. Ministers recorded births, baptisms, marriages and deaths. They also carefully tracked which families had moved to other towns and often described the reasons for moving. But along with tracking demographic and geographic change, in their descriptions of church meetings, the record books reveal, as no other source can, the unique conundrum that the English Puritans created in their colonies: a civil system that was incompatible with the Congregational ideal and reality that they had worked so hard to create.

“Church records reveal, as no other source can, the unique conundrum that puritans created: a civil system that was incompatible with the congregational ideal”

On the surface, this disconnect is invisible, cloaked by Congregationalism’s success. The denomination’s discipline developed in record time, with the first churches evolving practices in the 1630s and codifying them in the 1648 Cambridge Platform. The strength and reach of Congregationalism in Puritan colonies was foundational: the Puritans themselves defined their colonies as godly, while visitors and onlookers commented on the unusual importance, sincerity, and visibility of religion in the region. Every town had a meetinghouse, a minister, and a congregation. Congregationalism was supported by universal taxation and established as the state religion of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and it dominated the mental and physical landscape of Woodland New England for more than two centuries, from the Shawmut landing to Transcendentalism.

At the same time, it was incompatible with Puritan civil society, and this becomes visible in a set of double names: church/congregation and church/town. Every inhabitant of an English town was expected to attend worship services in the meetinghouse as part of the congregation of townspeople. But only those who could describe their experience of what modern Protestants would call salvation could be gathered into a church, a unique body called into being only by God.

In the church body, people relied on patient, long-term, multiparty mediation to come to full understanding of a problem and a satisfying, lasting resolution based on the restoration of all parties to mutual love and sympathy and healthy reunion. In the civil courts, however, the same people relied on rapid decisions made unilaterally by an unrelated authority figure who provided short-term resolutions that left one and sometimes both parties unsatisfied, nearly guaranteeing that they would return to the courtroom to argue the same case again, a zero-sum game played by individuals whose only goal was their own advancement.

“CONGREGATIONALISM WAS AN EVOLVING, LIVED EXPERIENCE MATTERING DEEPLY TO MANY GENERATIONS OF INDIGENOUS, BLACK AND ENGLISH PEOPLE, COMMUNALLY AGREED UPON”

Church records reveal how flexible and experimental Congregationalism was. For centuries in Woodland New England, it was an evolving, lived experience that mattered deeply to many generations of Indigenous, Black, and English people, a communally agreed-upon framework open to amendments, remarkably successful at making a spiritual ideal viable for real people living in the real world. Its records are a revelation of its co-created nature. Yet given the unavailability for these records for so many centuries, scholars have traditionally come to the reasonable conclusion that Congregationalism was 100 percent English and completely forced upon unwilling Indigenous and Black people. Now that so many church records are publicly available, it's time to come to a new understanding of Congregationalism’s mixed nature, as many scholars are now doing.

The historian Richard Boles, for instance, has documented the reality of Black and Indigenous participation in and affiliation with congregations in Woodland New England. He writes, “Most Americans today usually think of northern colonial churches as being entirely ‘white’ institutions, but black and Indian peoples regularly affiliated with these churches….” He argues that “most people experienced religion in interracial congregations.” Historian Margaret Newell writes in Brethren by Nature: “Together, English and Indians created a hybrid society in which Indian actions and goals sometimes determined the outcome.”

Today’s Grafton Unitarian Church, founded in 1731. John Phelan, Wikimedia Commons

The Congregational church body that the English created had surprising commonalities with principles common to the Indigenous society of the Eastern Woodlands, and the colonizing forces that overcame them represent a lost opportunity that we live with today. Many scholars ask whether, given the rapacity of English colonization in their homeland, how could any Indigenous person in Woodland New England willingly and sincerely convert to the colonizers’ religion? In fact, I believe it is important to reexamine both Indigenous andEnglish Christian practice. Each side had a majority who clung to pagan folk beliefs, mixing them into Christian doctrine or honoring them in parallel with Christianity. Each side had innovators whose lived practice of Congregationalism advanced and evolved that discipline. We can never look into the souls of Indigenous Congregationalists at the turn of the 18th century. But by looking at their practices and reading the accounts they left, we can honor them and also resist the urge to overwrite their words with our own assertions about what was possible and real for them.

Indigenous congregants shaped the evolution of Congregationalism in fundamental ways. For instance, the Wampanoag Congregationalists on Noepe/Martha’s Vineyard, for example, helped evolve the concept of assurance. While English Congregationalists relied on the mutual support and encouragement of friends and family to sustain them through the rigors of spiritual preparations, the moment of assurance of salvation they sought was something no one else could play any role in bringing about. English believers often testified to their reluctance to accept the positive judgments of their loved ones as hopeful proof of their own assurance. At first, Wampanoag converts adopted the English concept of an intensely solitary, internal, and private moment of realizing God’s grace, or salvation, a moment that one would then struggle to express to others. But over generations of their own practice, they redefined assurance as social and kinship-based. They understood the support and encouragement of their loved ones as representing assurance: that is, human kinship on Earth mirrored and anticipated divine kinship in Heaven.

This new understanding actually hewed closer to the Puritan requirement that no “human invention” be used in Congregationalism, and every part its practice be derived from the Bible or the apostolic church, for English-style assurance was a very human invention found in neither source. Wampanoag assurance recovered the apostolic spirit of finding hope in the fellowship of believers and refocused church gathering on shared belief and spiritual kinship rather than individual proof of grace. This is just one example of the several ways that Indigenous people fully participated in, and shaped, Congregationalism, making it their own.

The full communion record of Elizabeth Abraham, Nipmuc, on July 13, 1740, as noted in the Hassanamisco church book, 1731-1774, in the Grafton, Massachusetts, Evangelical Congregational Church records, RG 4921, Congregational Library & Archives, Boston

Congregationalism successfully brought an untried, very ambitious religious ideal into real-world practice when that real world was, for both the colonizing Puritans and the Indigenous people who suffered colonization, unknown and dangerous and should have ruled out any spiritual experimentation. Congregationalism was an Indigenous-English collaboration, and the hobbling of the Congregational ideal was a tragic lost opportunity for the English to escape the mania of colonization, allow personal points of contact, develop reciprocal relationships between themselves and Indigenous people, and join those people in honoring the obligations of kinship, not only with each other but with the land, water, and living creatures of the Eastern Woodlands. Their complete failure to do any of this makes it seem as if such an opportunity could never have existed.

Only by reading the church records can we see that the Congregational ideal, with its kinship and its obligations to building relationships, not fortunes, actually created positive outcomes that contrasted sharply with secular civil outcomes. They show us that a different path did exist. People travelled on it. The opportunity was there. We can learn something from the story of how that opportunity was lost, and perhaps our knowledge can move the needle even a fraction against the problems we are reaping now.