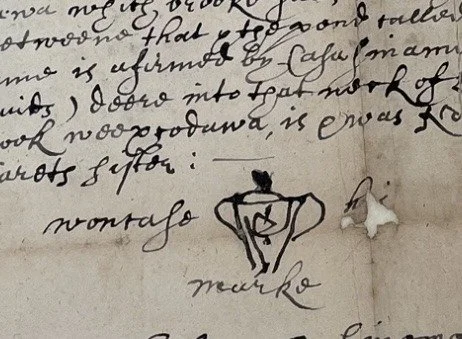

their marks

The erasure of Indigenous people from traditional accounts of New England’s history, or their relegation to the role of those who simply greeted colonists from across the sea, is well known - their place taken by the “first” settlers in places such as Boston, Concord or Plimoth. There is a further myth that Native people were never documented in the written record. But as this blog post shows, Indigenous people of the Eastern Woodlands were present - and present in documents everywhere. Based on a stunning new and ongoing Instagram project, Their Marks, it presents the signatures - or “marks” - of Indigenous people throughout the 17th century. Their Marks is a project of Kimberly Toney, coordinating curator for Native and Indigenous materials at the John Carter Brown Library and the John Hay Library, Brown University.

The Partnership of Historic Bostons presents here Kim Toney’s discussion of Their Marks, together with a selection of twelve signatures of Indigenous people caught up in King Philip’s War, Native people’s resistance to the colonial destruction of Native lives, livelihoods and sovereignty.

Follow Their Marks on Instagram @theirmarks and Tumblr.

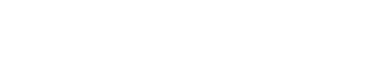

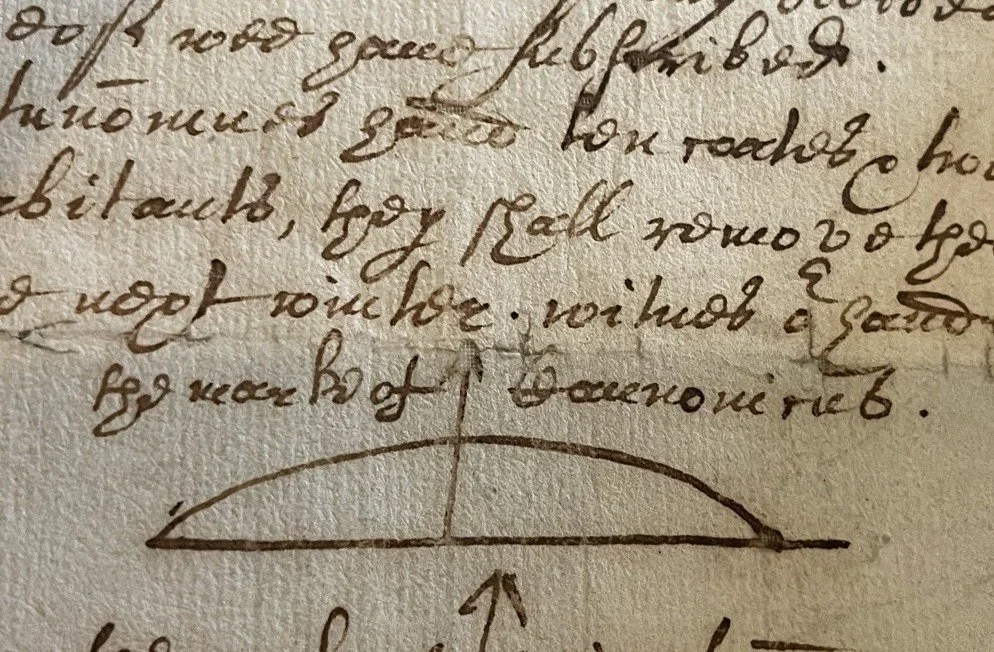

The mark of Metacom, or Philip, on a quitclaim deed signed in Rehoboth, MA. From the collections of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence RI. Photo courtesy of Rythum Vinoben

Their Marks is a Native-led archival and public history project that centers pictographic signature marks Indigenous people left on land deeds, petitions and other legal documents in the 1600s and 1700s across the Native Northeast. These documents – often labeled “Indian deeds” and written in dense English legal language – were tools of settler colonialism used to take Indigenous land and reshape the Dawnland - the region now called New England. But, they also hold something else: the marks - pictograph signatures, names, and relationships - of Native people who were always here.

These signatures, or marks, take many forms - letters, animals, people or features of the land. Indigenous people used them to represent themselves in documents created under unequal and hostile conditions, usually drawn up with the help of translators and within European legal systems. Rather than seeing these marks as signs of loss or disappearance, Their Marks treats them as intentional acts of self-representation. They show Indigenous presence and agency even as the terms of land “ownership” were being violently transformed. The marks are evidence of survivance: ways of asserting existence and engagement within a system never meant to honor, recognize or validate Indigenous life or ways of being.

“Marks are evidence of survivance: ways of asserting existence within a system never meant to honor indigenous life.”

Their Marks is grounded in ongoing archival research in libraries, historical societies, and state archives across Massachusetts, southern New England, and beyond. Each entry focuses on one mark and the document it appears on, paying close attention to kinship ties, leadership relationships, Algonquian place names, and the specific exchanges recorded on the page. Some individuals - such as Metacom or Weetamoo - are familiar from regional histories, especially in the retelling of the War for the Dawnland (also known as the First Indian War, King Philip’s War, Metacom’s Resistance, and others).

Many other names and signers appear only once in the historical record, their lives reduced or erased by the archive and collective memory. Their Marks does not attempt to tell full biographies or resolve archival silences. Instead, it stays with what the documents can show and asks why so much Indigenous life in places throughout New England has been made so hard to see.

“their marks is defined by centuries-old primary documents… but it is ultimately about the present and future.”

Language and land are deeply connected in this work. Early documents often include Algonquian place names - descriptive, relational names that reflect long-standing relationships between people and place held across millenia. Over time, many of these names were replaced with English ones, further erasing Indigenous presence and relegating it to a romanticized past. Bringing these names back into view is one way of remembering that Indigenous history in the Dawnland did not end in the 17th century. It is ongoing and everlasting.

While Their Marks is defined by archival research and the examination of centuries-old primary documents, it is ultimately about the present and future. The same papers that transformed Indigenous relationships to land still shape today’s neighborhoods, borders, and institutions. The project does not try to redeem the archive or offer closure. Instead, it invites careful examination and asks us to look closely and think critically: What do you see in these marks? What do they make visible? How do the histories of this land continue to shape where you live? And what responsibilities come with knowing all this?

“What do you see in these marks? What do they make visible? What responsibilities come with knowing all this?”

Pometacom. Metacomet. Metacom. King Phillip. His mark in the 1670s.

From the collections of the John Carter Brown Library, Providence, Rhode Island.

Wampanoag. His homelands at Pokanoket. Born 1638. A Wampanoag sachem by 1662, after his brother's suspicious death. A diplomat and strategist. Led a confederation of Eastern Woodlands tribes in a rebellion against colonizers in the War for the Dawland, 1675-1676. Fought to reclaim sovereignty, resist subjugation and dispossession, and for landback.

Assassinated August 12, 1676 and dismembered upon his death. Colonizers displayed his head on a spike at so-called Plymouth for over two decades.

Kin: Father Ousamequin, the Massasoit. Brother, Wamsutta (Wamsutta’s partner, Namumpum - later called Weetamoo). Partner, Wootonekanuske.

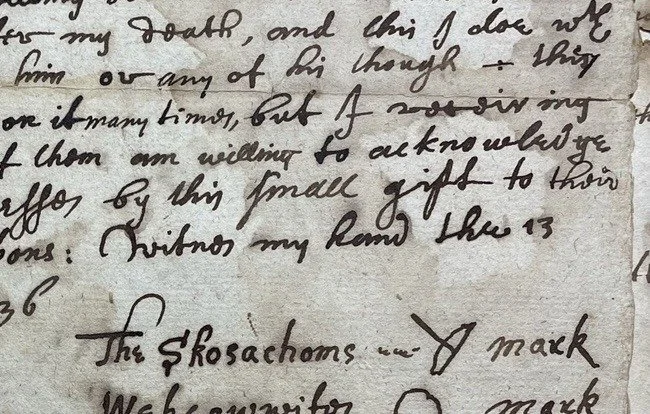

Squaw Sachem. Squaw Sachem of Mistick. Saunkskwa of Missitekw. Skosachoms. Her mark in 1636.

This November 13, 1636, land deed (recorded in 1656) signed by Skosachons is for a tract of land from so-called Charlestown and Cambridge, Massachusetts, “against the ponds at Misticke” to Jotham Gibbons. Massachusetts Historical Society

Massachusett. Her homelands spreading across the areas of present day Charlestown to Concord, MA and across Massachusett, Nipmuc and Pawtucket territories. Leader across several Massachusett and Pawtucket communities before, during and after the death of her first partner, Nanepashemet (d. 1619). She died in 1667.

Kin: A partner, Nanepashemet. Sons, Wonohaquaham (or Sagamore John), Montowampate (or Sagamore James), and Wenepoykin (or Sagamore George). Partner, Wompachowet or Webcowit. Daughter, Yawata (or Sarah).

This post offers an opportunity for reflection and discussion around the appropriation and derogatory meaning the Algonquian word (and once honorific term) “squaw” or “sonksqua” now holds. This document also calls to attention the lack of documentation of this leader’s Massachusett name. Despite her mark appearing on many ‘legal’ documents in the 17th century, her given name was never recorded. Perhaps Saunskskwa/Sonksqua was her chosen identity; perhaps colonizers weren’t concerned enough to record her other name(s).

Canonicus. His mark in 1637.

This March 24, 1637 deed signed by Canonicus describes land on the island of “Acquidneck” and north to “Kitackamuckqutt.” The islands of Aquidneck, and the areas of Kickemuit and “the grass upon the rivers and coves about Kitackamuckqutt” and to Paupausquatch were exchanged for “40 fathom of white beads” plus ten coats and twenty hoes. Narragansett inhabitants of the island were then told to “remove themselves” before the next winter. Massachusetts State Archives

Narragansett. Sachem of the Nahaganset (Narragansett). His home along the shores of Narragansett Bay, in so-called Rhode Island, and into so-called eastern Connecticut. Born about 1565, died June 4, 1647. Initially a dubious opponent of colonizer settlement upon the arrival of the Pilgrims, Canonicus later signed a peace treaty with colonizers in 1644 - presumably in the pursuit of the survival of his nation.

Kin: A descendant of Tasshasuck. Brother, Mascus. Nephews Miantonomo and Pessicus. Son, Mixan (Mixan’s partner, Quaiapen).

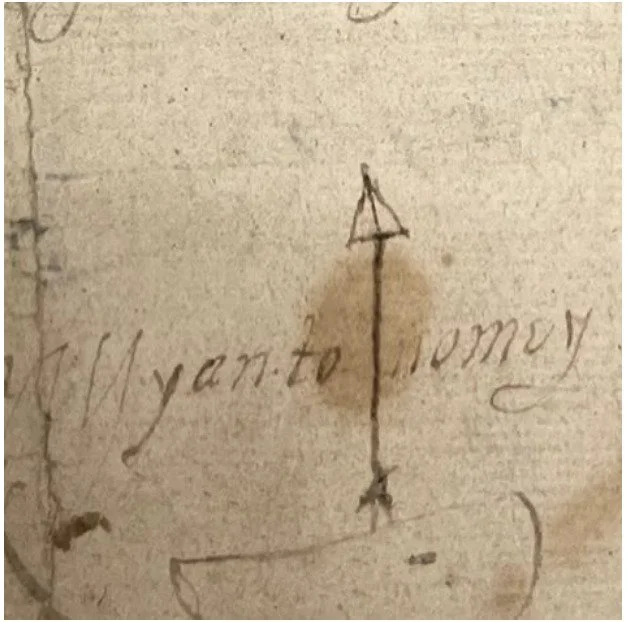

MIANTONOMO. miantonomoh. myantonomy. his mark in 1642.

Indian deed signed in 1642 by Miantonomo in Warwick, Rhode Island. John Carter Brown Library, Providence, RI

Narragansett. His home along the western shores of Narragansett Bay, in so-called Rhode Island, and into so-called eastern Connecticut. Sachem. In 1640s, appealed to sister tribes to create an alliance against colonizers. Brought to Mass. Bay Colony in 1640 on charges of conspiracy against settlers. Executed in Mohegan territory in 1643 following tensions with Mohegan sachem, Uncas and the English.

Kin: Father, Mascus. Uncle, Canonicus. Brother, Pessicus. Son, Canonchet. Partner, Wawaloam.

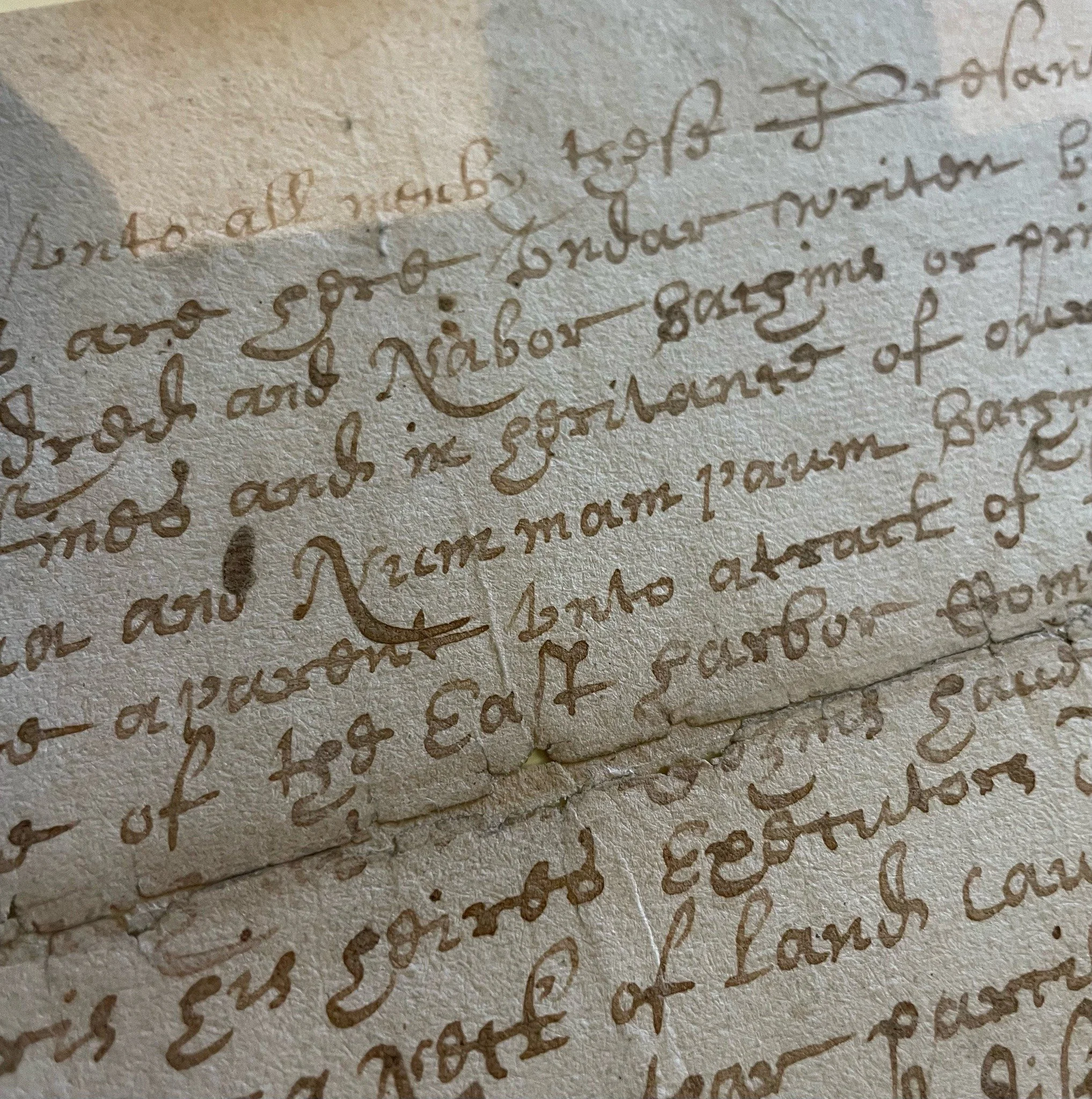

Osamekins Chefe Satchim. Ousamequin. Massasoit. Their mark in 1651.

In this deed signed July 26, 1651 by Ousamequin and other “nabor satchims” acknowledge the sovereignty and leadership power of their “beloved cosin” Nummampaum (Weetamoo) in her own territory at Pocasset. Massachusetts Historical Society

Pokanocket, Wampanoag. His home at Sowams, on present-day Wampanoag homelands and in the southeastern parts of so-called “Rhode Island and Massachusetts.” As Great Sachem or Massasoit of the Wampanoag, Ousamequin led the people of the first light through the time of the great plague (1616-1619) and signed a treaty with European settler-colonizers in 1621, just after those settlers first arrived to the shores of Wampanoag territory.

Ousamequiin continued to navigate a tenuous relationship with colonizers until his death in 1661. (Ousamequin means yellow feather in the Wampanoag dialect of the Algonquian language.)

Kin: Sons, Wamsutta, Pometacom and Sonkanuhoo. Daughters Amie and another whose name is currently not known.

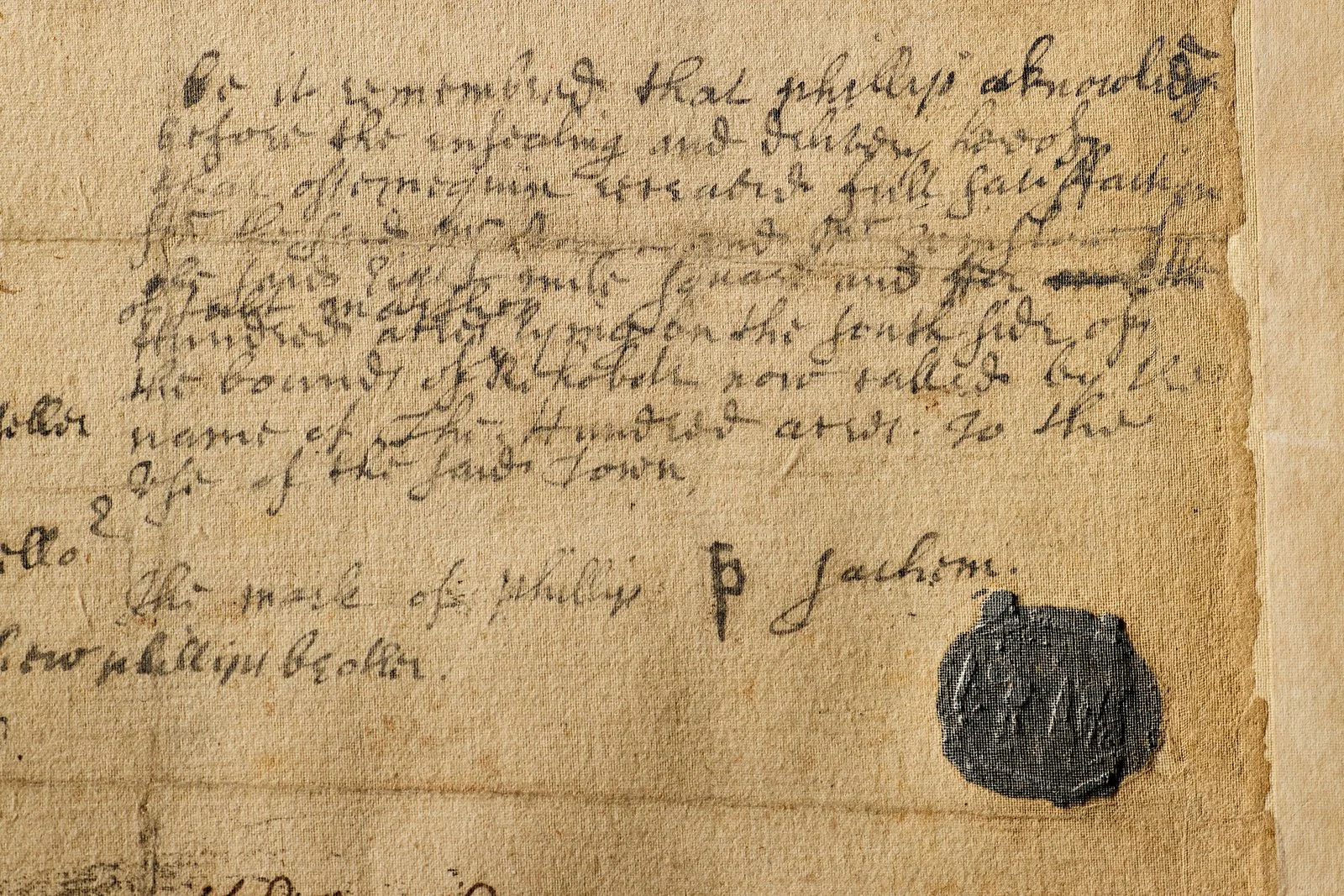

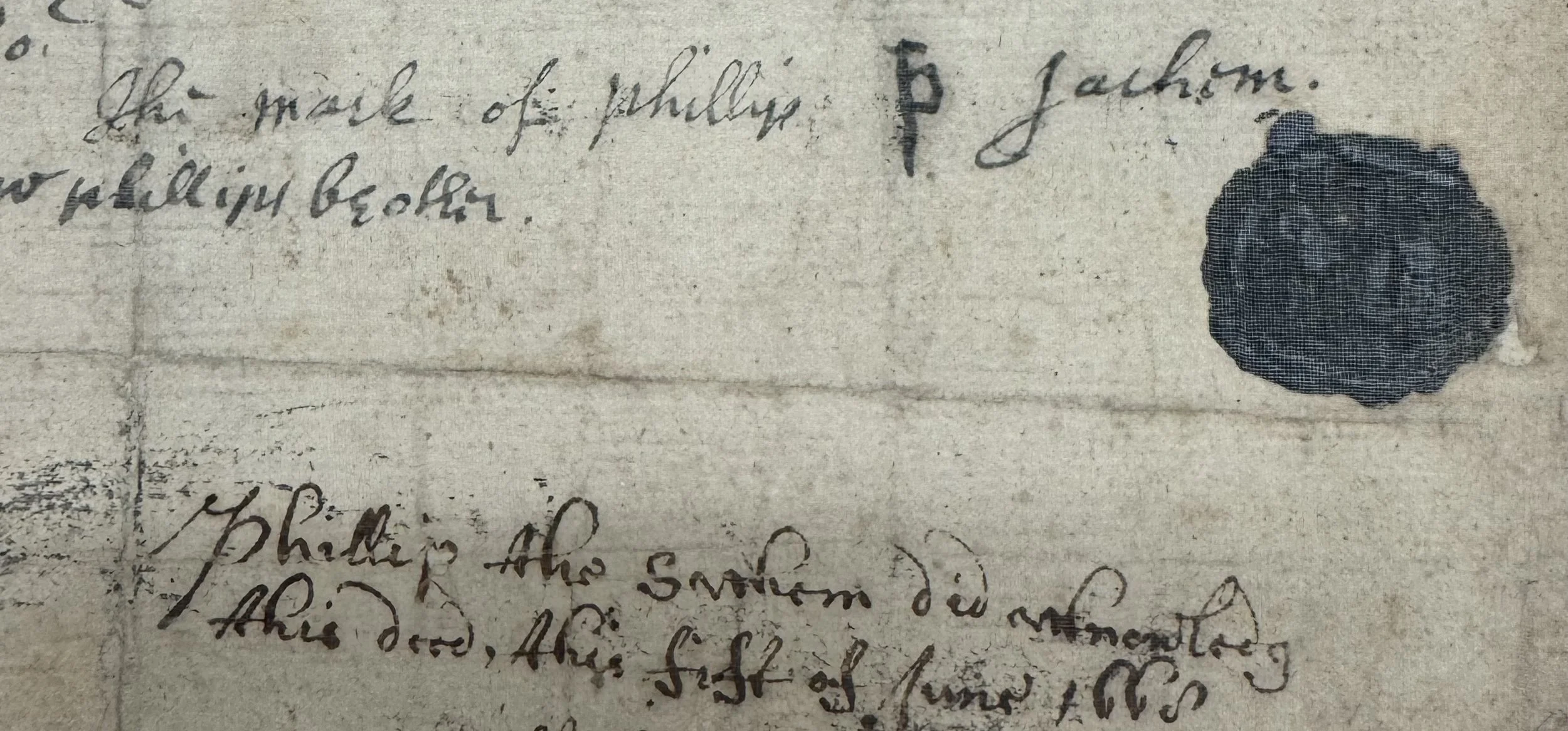

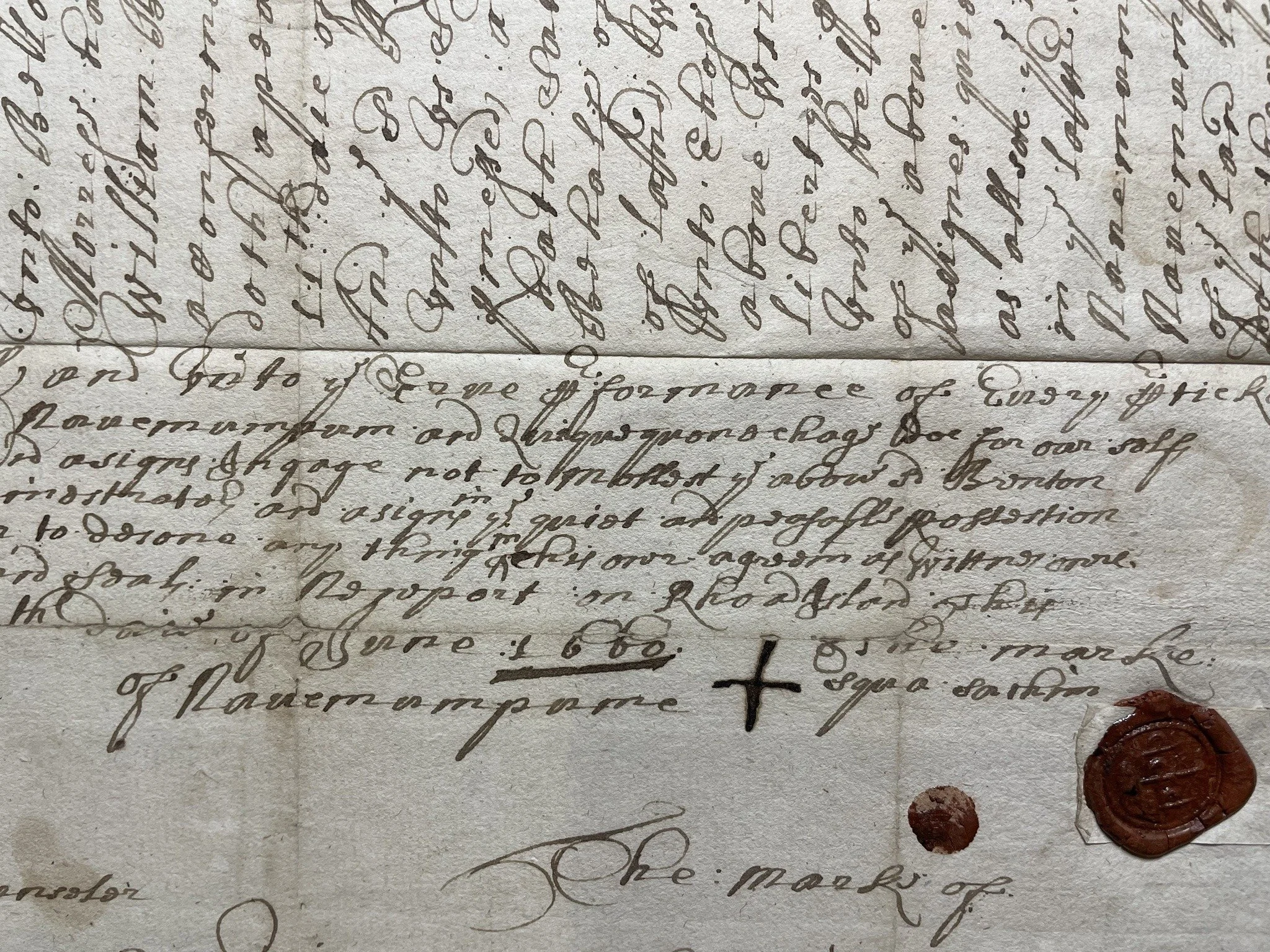

Weetamoo. Tatapanunum. Namumpum. Nauemampome. Their mark in 1660.

This deed was signed by Weetamoo in June 1660. Massachusetts Historical Society

Wampanoag. Sachem of Pocasset. her homelands present day “Tiverton, Rhode Island,” Quequechan or “Fall River, Massachusetts” and surrounding areas. Kinship ties throughout Pokanoket, Wampanoag, Massachusett, Narragansett territories. During the War for the Dawnland, led raids against colonizers throughout Nipmuc, Massachusett and Wampanoag homelands. In 1676, her body found in the Taunton River, then dismembered by colonizers and displayed for public view at so-called “Taunton, Massachusetts” for two decades. Two decades.

Kin: Father, Corbitant. Sister Wootonakanuske. Partner, Winnepurket. Partner Wamsutta (brother of Pometacom and son of Ousamequin). Partner, Quequequanchet. Partner, Petonowowetta. Partner Quinnapin (son of Ninigret).

Uncas. Poquoiam. Woncase. His mark in 1662.

This August 4, 1662 document outlines the areas Uncas considered to be “Pequid” lands. Massachusetts State Archives

Mohegan. Sagamore of Mohegan. Born ca. 1590, his homelands at Shantok and across some southeastern parts of present-day “Connecticut.” Descendancy and kinship ties across Narragansett and Pequot communities. Present at the Massacre at Mystic Fort, responsible for the execution of Narragansett sachem Miantonomo. Died ca. 1683.

This document, also signed by Robin Casasinamon, asserts that Pequot homelands [a time before the colonizers stole the land], extended “to a brooke called weexcodawa…unto the end of that water or pond called nekeeequoweese…the land falling betweene that & the pond called teapanocke.” The signed document continues on to say the land “eastward of the brook weexcodawa is & was Naraganset Land belonging to Ninagras and his heires.”

Kin: Parents, Owaneco (I) and Mekunump. Sons, Owaneco (II), Attawanhood (II) or Joshua, and Benjamin Uncas.

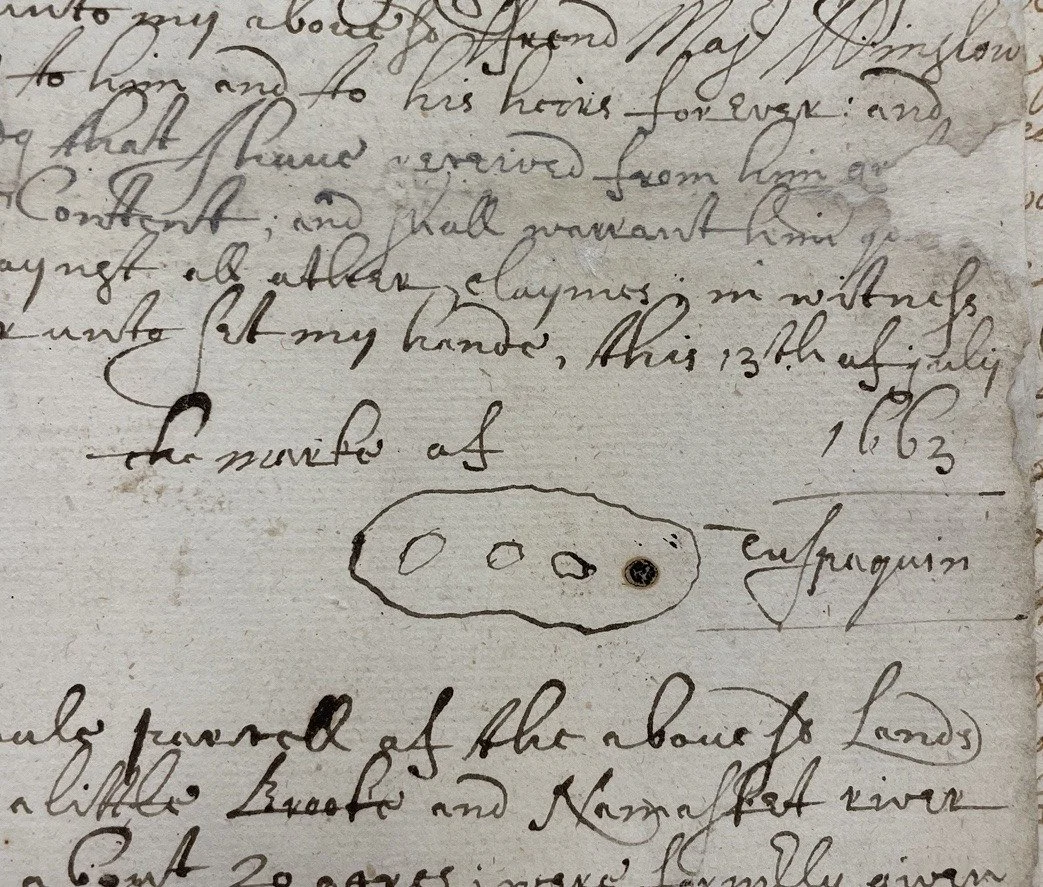

Tuspaquin. His mark in 1663.

This deed signed July 13, 1663 discusses land at Nemasket. Tuspaquin identifies as “Tuspaquin (alias) the Black Sachem of Namassakat.” [American Antiquarian Society]

Wampanoag. Homelands at Nemasket and Assawompset (in the areas today called “Middleboro” and “Lakeville, Massachusetts”). Fought alongside Metacom in the War for the Dawnland and was executed by colonizers in September, 1676.

Kin: Father, Pamontaquask. Partner, Amie (daughter of Ousamequin and sister of Pometacom and Wamsutta). Sons, Benjamin and WIliam Tuspaquin.

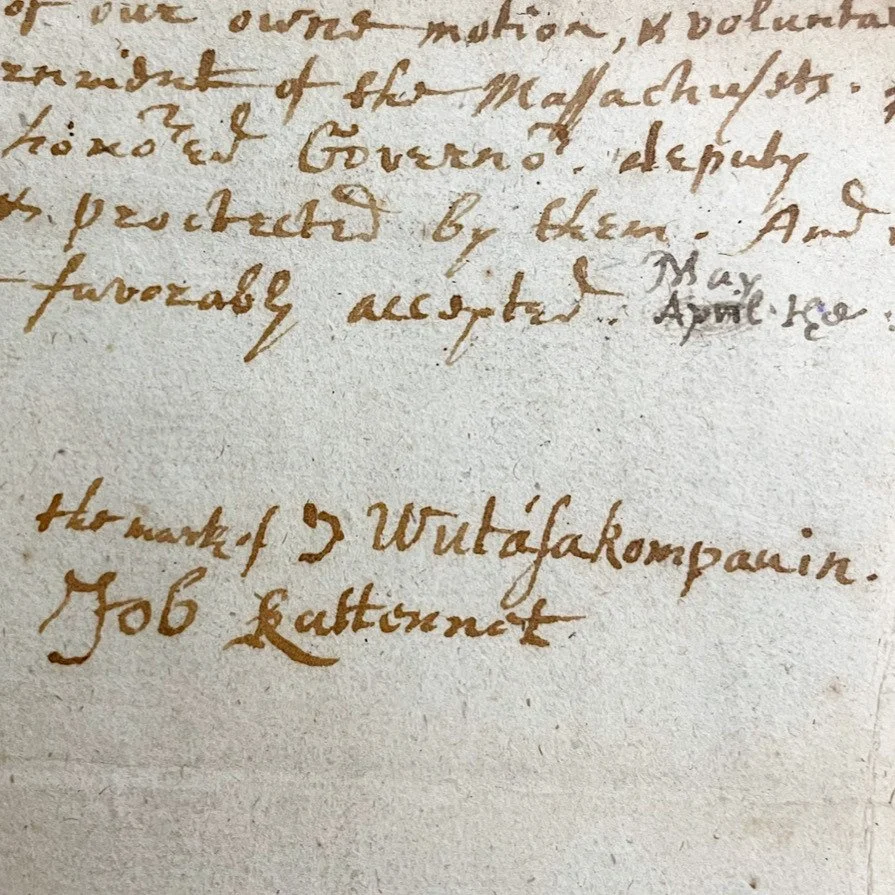

Wutasakompanin. His mark in 1668.

This 1668 document reports to be submitted on behalf of “peoples of Nipmuck…the inhabitants of Quánutusset, Mônuhčhogok, Chaubunakongkomuk, Asukodnôcog, Kesépusqus, wabuhqushish and the adjacent parts of Nipmuk…” It pledges the submission of inhabitants of praying towns to the government of Massachusetts. Below Wuttasacomponom’s mark is the signature of Job Kattenanit, brother of James Printer. Massachusetts State Archives

Nipmuc. Also known as Captain Tom or Tom Wuttasacomponom. A Christian convert at Hassanamesit. Vowed loyalty to settlers during the War for the Dawnland but was still hung by colonizers in 1676 after accusations of being involved in the burnings of Sudbury and Medfield (which Wuttasacomponom denied).

Kin: Son, Nehemiah Tom.

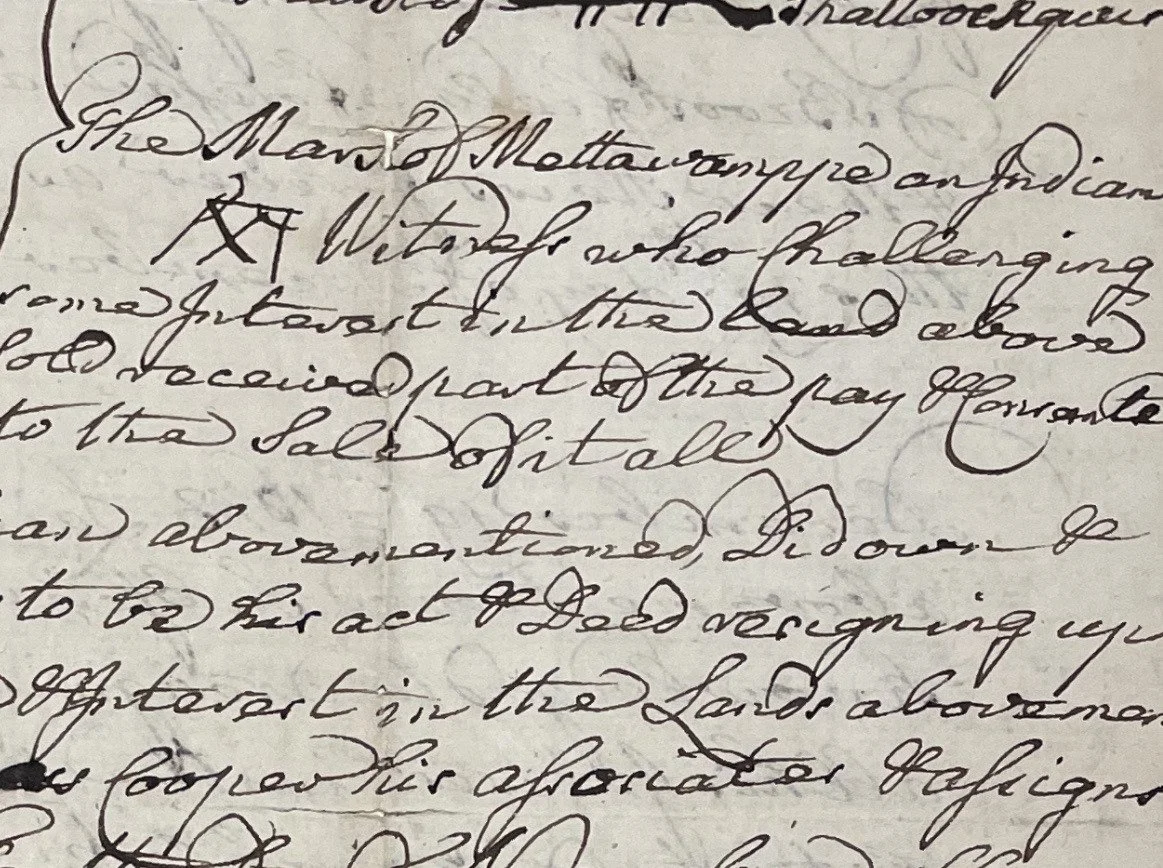

Muttawamp. Mattawmp. His mark in 1673.

Mattawammppe’s mark, a thunderbird, seen here on a deed from 1673 for lands at Quabog. Muttawamp appeared to challenge the sale of the land, staking claim for his own interest in the transaction. Brookfield, MA Papers. American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts

Nipmuc. His home in and around Quabog, (present-day New Braintree, the Brookfields, and surrounding areas), part of Memamesit.

Led attacks at New Braintree and Brookfield (or Wheeler’s Surprise + the Brookfield Siege) against Massachusetts Bay Colonizers in August of 1675. Led attacks at present-day “Sudbury,” “Hadley,” “Hatfield,” and “South Deerfield” (Battle of Bloody Brook), Massachusetts, during the War for the Dawnland. Mugquompoag (military leader). Executed by colonizers in September 1676.

Place names used in this document: Masquabanick, Nanantomqua, a hill called Asquooch, a brook called Naltaug, Quabaug, Podunk, Lashaway, Massaquoukcumis, Nacommuck, Wullamannuck, Masgpabbanisk and a hill called Agnoack.

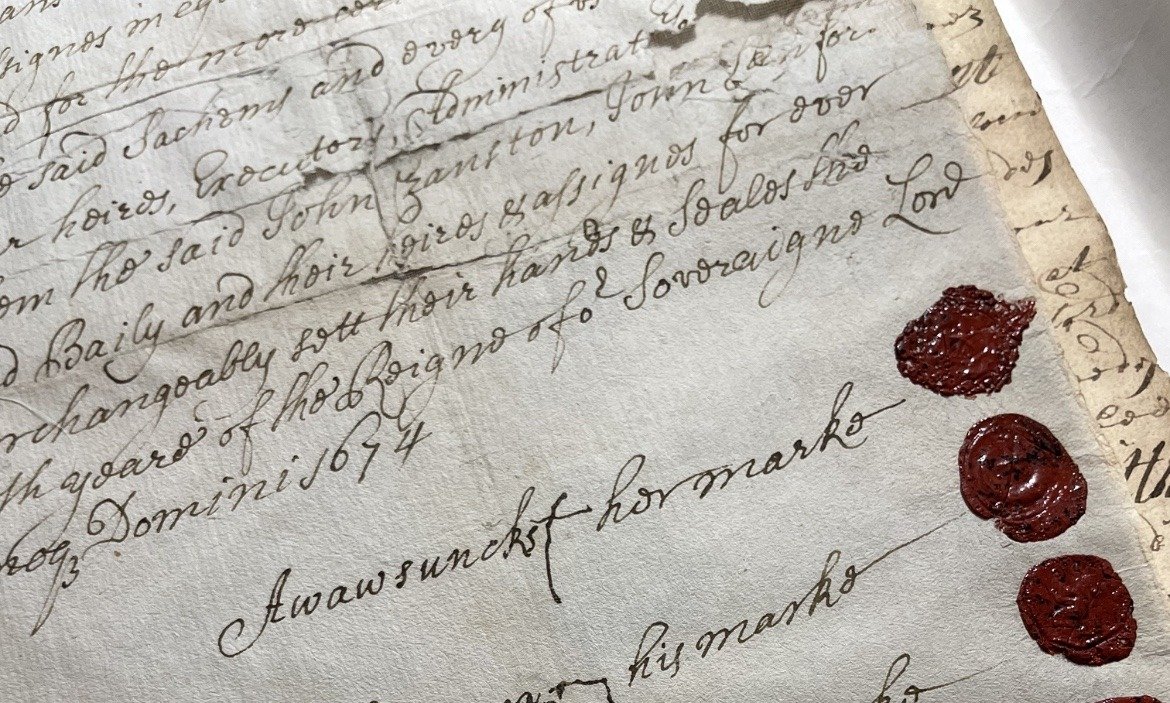

Awashonks. Awawsuncks. Her mark in 1674.

This May, 1674, document signed by Awashonks is for Sakonnet land. Massachusetts Historical Society

Wampanoag. Sachem of the Sakonnet. Her home there, near Narragansett Bay and Patuxet, in and around the place known today as Little Compton, Rhode Island. Created a hopeful alliance with colonizers at Plimoth to spare her people from enslavement during and after the War for the Dawnland. Endured the dispossession of lands and several attempts by colonizers to usurp her role as leader at Sakonnet.

Kin (also appearing on this document): Samponock (alias Amos), Wawwooyowwitt, Soonchas (identified as her son). Names spelled as they appear.

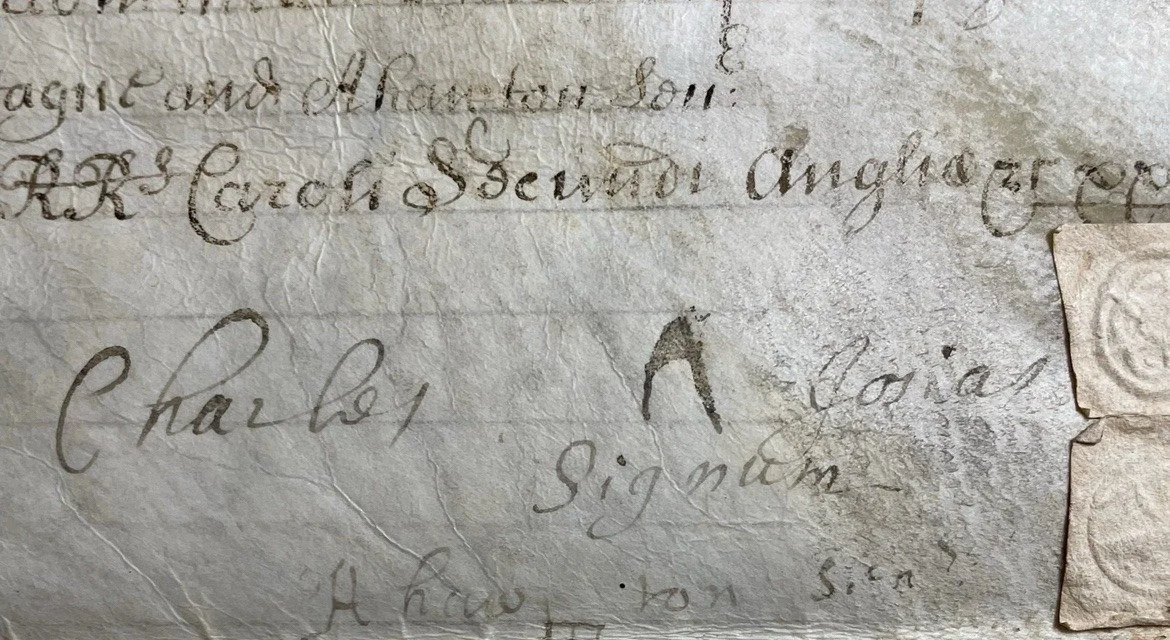

Charles Josiah Wompatuck. Charles Josias. His mark in 1684.

This document signed March 19, 1684, is referred to as a quitclaim deed for the peninsula of Boston. Massachusetts Historical Society

Massachusett. Ties to Mattakeeset, Neponset and Wessagusset communities, in the areas south of the place today called “Boston, Massachusetts.” Sachem by 1671. Died after 1695. Translated from the Algonquian, wompatuck means “white deer” in English.

Kin: Father, Josiah Wompatuck, Sachem at Mattakeesett. Grandfather, Chicatabut, Sachem at Wessagusset. Great-uncle, Cutshamequin, Sachem at Neponset.