From paradise to prison

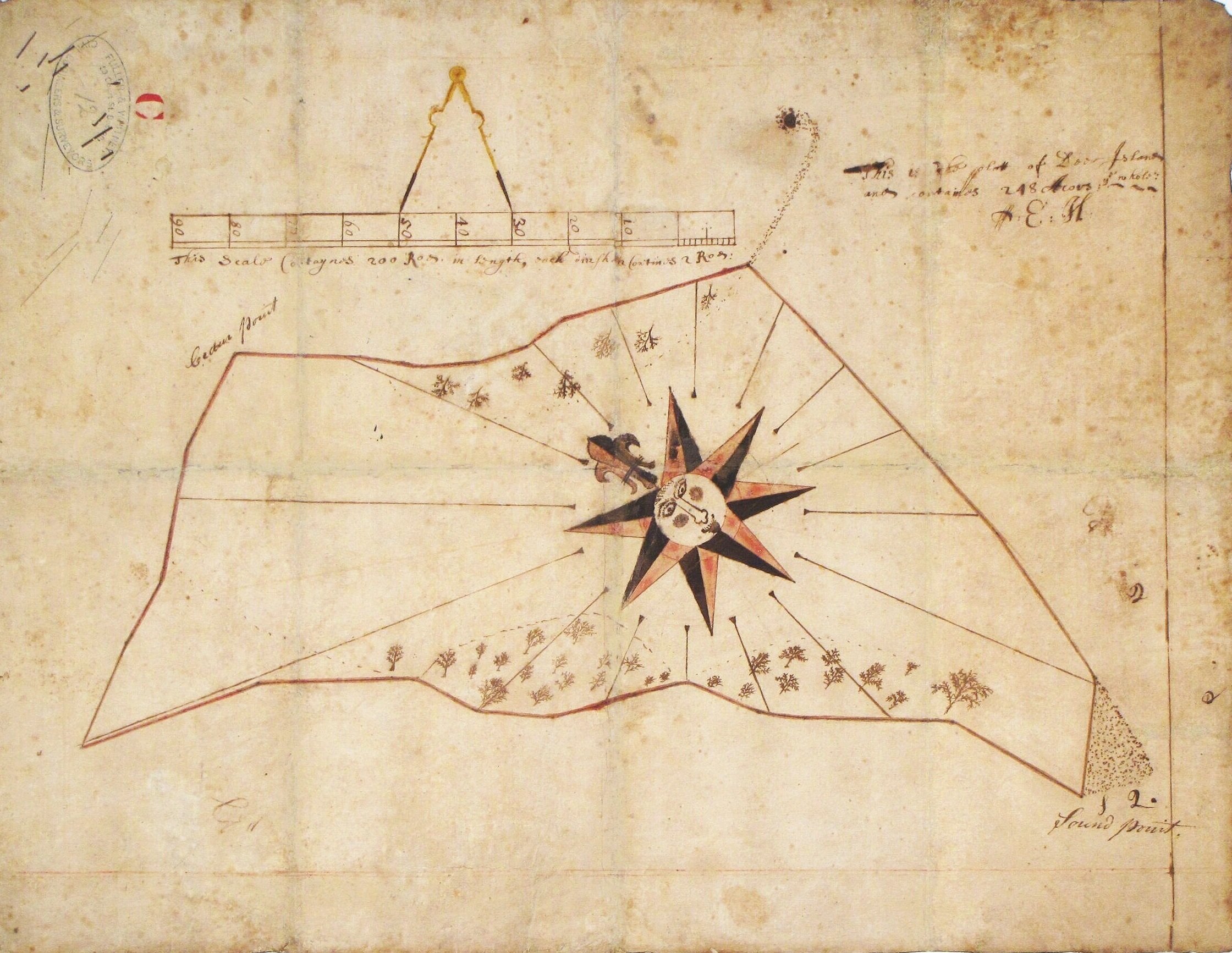

A c.1700 survey of Deer Island, possibly part of an attempt by the town of Boston to settle its claims to Native lands. Image courtesy of Boston Rare Maps, Southampton, MA

When Captain John Smith sailed down Maine's coast to the bay of the Shawmut peninsula and entered quonehassit, or what we now know as Boston harbor, he passed some of the summer places of the Native people. These beautiful and well-tended islands were farmlands for Native crops and fishing grounds for seafood. Deer Island was among them, large, bustling with activity, full of thriving mounds of corn; it would have been difficult to miss the presence of Native people. It is easy to understand why Captain Smith called these islands "the Paradise of all these parts." They were fertile, beautiful, surrounded by tidewater estuaries, overflowing with life.

Like the other Boston harbor islands, Deer Island provided many of the Massachuset people ample space to plant, nurture and harvest crops that fed them through the harsh winter months. These islands were treasures, carefully tended to by extended families of tribal women from early spring until the fall harvest. The intercropped mounds of corn, beans, and squash were staples of their healthy diet. They gathered the islands’ berries and other plants for food and medicine. In the fall, as was customary in Native culture, they carefully put the islands to rest, cleaning up remnants of their crops, returning the land to a peaceful state for the winter resting period.

Indeed, this was a paradise. How could it come to pass that, just a few decades after the Puritans arrived in 1630, their "Paradise" would be lost forever? These islands, Deer Island principal among them, were transformed during King Philip's War into camps for indigenous people who had only known these Islands as bountiful and life-sustaining places. In the winter of 1675-76, Deer Island became a prison camp.

“THERE IS NO SAFETY FOR US [ON DEER ISLAND], BECAUSE MAYBE THE ENGLISH COME TO KILL US…”

- Praying Indians from Wamesit

Paradise’s end

The beginning of the end of this paradise can be traced to 1614, when Captain Smith drew his map of the coast, naming it "New England." He did this to further English imperial aims, and to attract English colonists who could claim it as their own. Like all 17th century explorers, he disregarded the inherent sovereign rights of the original people of this place now on the map as New England. In 1629, the English crown created the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter which, as an act of Charles I, granted permission to establish a permanent colony in the land of the Massachuset.

Relations between the Puritans and the Natives were uneasy from the outset. Still, there were many attempts at cooperation. After all, this was not the first time that Native people had accommodated others who "did not belong to this place." The exploration of the Massachuset lands might have begun as early as 1000 AD. Norwegian scholars believe that Leif Ericson visited and may have even wintered here. In 1002-3, Ericson's brother Thorwald visited the coastal areas of the Massachuset, forming trading agreements, diplomatic ties, and commerce with the tribes. Others also began trade agreements with various tribes nearly 200 years before Columbus attempted to reach Turtle Island and more than 300 years before the Puritans arrived.

The land was a paradise…. The portrait of an unnamed Native American sachem, painted in European style c.1700. Image: RISD Museum, Providence RI

Clash of conceptions

But the arrival of the Puritans was different. With charter in hand, they came to establish a permanent settlement: the Massachusetts Bay Colony, predicated on a belief that the English had right to claim the Massachuset homeland for themselves and the crown. With little or no understanding of the English concept of private land ownership, tribal sachems attempted to bring the English into their kinship networks, with the belief that the colonists would embrace and participate in tribal eco-systems. Few newcomers acknowledged tribal rights of natural inheritance.

Indigenous people had no concept of individual private land ownership. Tribal leaders, sachems, and squaw sachems permitted what they believed were land-use and occupancy rights. The English understood this permission as binding agreements, titling and conveying private land ownership that permanently alienated Native people from their traditional hunting, fishing, and farming lands.

“Obedience of the onlie true God”

Most Puritans, moreover, were convinced that they had their God's favor. They saw themselves as having been chosen by their God to establish what their leader, John Winthrop, declared to be a shining “Citty upon a Hill,” a closely knit Christian community bound by God and their Puritan faith. Ironically, they dismantled the original hills of the Shawmut peninsula. While they thought Native people would never be their equal, the colonists believed it their mission to convert the "heathens" to Christianity. A section of the charter specifically instructed the Puritans "[t]o winn and incite the native of the country to the knowledge and Obedience of the onlie true God and Saviour of Mankinde, and the Christine Fayth." But as the decades passed, the colonists increasingly portrayed Native people as idolatrous, godless savages.

The Eliot Bible, the first book to be published in America, in 1663. The Rev. John Eliot translated the Bible into Massachuset so that he could evangelize and convert Native people. Ironically, it was later used to help recover the Algonquian language.

Eliot’s praying towns

The speed with which the Puritans acquired land as private property, displacing Native people, was astonishing. The Boston harbor islands counted among lands appropriated by colonists, with Noddles Island (now part of east Boston), for instance, “granted” by the Massachusetts General Court to Samuel Maverick in April 1633. By 1646, a growing number of Natives were expelled, fenced off, and barred from the land. To fulfill part of the charter's mission, the Puritans began to convert the heathens to Christianity, and appointed John Eliot, a Puritan minister from Roxbury, as a missionary to the Natives. He translated the Bible into the Massachuset language, and preached in Massachuset at Nonantum, present-day Newton. And he set about creating special towns - “praying towns” - with the specific goal of converting Natives to Christianity.

In return for the relative safety and stability of these praying towns, Native peoples had to accept European customs. They also had to give up what they had known, believed, and practiced in their tribal villages, including their traditional clothing, rituals, spirituality, language, and customs. Between 1651 and 1675, Eliot successfully established 14 of these praying towns with notable locations at Natick, Punkapoag, Hassanamisco, Nantucket, and Mashpee. Most colonists believed the Natives living and working there were Christ's followers.

FAMILIES WATCHED AS THEIR KIN DIED, IN THE COLD, IN PAIN, OF STARVATION AND EXPOSURE.

In the summer of 1675, after 55 years of uneasy cohabitation, the transformation of land into private property, and the displacement of Native people, things reached a tipping point. Many remaining Indigenous people were unable to contain their anger with the English. In June of that year, a conflict erupted known as King Philip's War, which was part of a greater engagement that the Massachusetts minister Increase Mather entitled "The Warr with the Indians in New England." This war would be one of the bloodiest and costly conflicts for both Natives and settlers.

Metacom, King Philip, was the son of the late Pokanoket chief sachem Ousamequin Massasoit. He and his warriors were unrelenting in their quest to regain their lost territories. He intended to expel the English forever. The English mounted a formidable defense, but at the onset, Metacom had the upper hand. Settlers across New England were terrified by the threat of attack. By the time that Metacom lost the war and his life, he and his warriors had razed 25 colonial towns, leaving them in ashes and ruins.

Some praying town Natives defected to join Metacom. Others, like those those in Wamesit, left their town for French territory: “As for the Island,” they wrote in a letter quoted by Jill Lepore in The Name of War, “we say there is no safety for us, because many English be not good, and may be they come to us and kill us…. The English have driven us from our praying to god…” The people who remained in the praying towns were loyal to Christianity and the English. But colonists feared that they too would revolt and join Metacom. Whether or not the remaining praying Indians would have been a threat will never be known. By the fall of 1675, as more stories of carnage and destruction reached the colonists, many pressed the Massachusetts authorities to imprison Eliot's praying Indians.

From paradise to prison camp

Fear makes Christian men and women think of and commit ungodly acts against other human beings, and on October 13, 1675, the mandate from the Massachusetts authorities was enacted. Motivated by deep mistrust and fear, the court ordered the immediate relocation of all Christian Indians in Natick to Deer Island, with the other towns to follow. They were summarily rounded up, unable to take much besides the clothes on their back, marched across their ancestral lands, now almost entirely unrecognizable to them, and imprisoned on Deer Island for the duration of the war. In an act of unthinkable cruelty, up to 1,000 Natives were moved to the islands - including a significant number from the Nipmuc nation and the Ponkapoag, the latter imprisoned on Long Island. The winter was setting in, and we now know that the planet was experiencing what scientists are calling the “little ice age," making the already bitter and biting cold Islands that much more deadly.

“THIS PARADISE ISLAND WAS NOW A war-time CONCENTRATION CAMP”

The prisoners of war on barren Deer Island must have been shocked by their betrayal by those they had considered fellow-Christians, and were starving, weak, and freezing. Ironically, their descent into starvation was documented by colonists including John Eliot and Daniel Gookin, who sympathized with the Native plight but could do little to aid them, and by those sent to oversee Deer Island by the authorities. But many in the colony felt that imprisonment did not go far enough; the prisoners needed to be destroyed. In February 1676, Abram Hill, a settler in Malden, asked the Rev. Thomas Shepard to accompany him and 30 other men to invade Deer Island one moonlit night, and kill every person there. Shepard informed the Massachusetts Council, which blocked Abram’s plan. But it indicated the depths of hostility and desire for a scorched-earth war.

Death, slavery, and survival

Even without a massacre, Christian Indians on Deer Island died by the hundreds. Left without adequate shelter, food and the means to fish from the bay, this island, "the Paradise of these parts," was now a concentration camp - a witness to the slow and painful death of those who belonged to this place. Family watched, unable to help as their kin slowly died, in the cold, in pain, of starvation and exposure during a cruel and unforgiving winter. Despite knowing of the harsh conditions, their captors did not sufficiently ease their captives’ imprisonment. More than half the people interned on Deer Island died over the winter; others were sold into slavery in the West Indies. Those who survived returned to reservations (as the consolidated praying towns came to be known) in the colony. Their descendants, the Nipmuc and the Massachuset tribe at Ponkapoag, live on today.

King Philip's War ended in the crushing defeat of Metacom and his warriors in August 1676, when he was gunned down at his home at Mount Hope. This defeat was catastrophic for indigenous people everywhere in New England. In the aftermath of the war, they were hunted down, beaten, imprisoned, and killed, run off their homelands, and relegated to designated Indian reservations. Many were sold into slavery. The outcome of this war determined the fate of Native people in New England and ultimately the destiny of a land that would later become the United States of America, at the cost of indigenous peoples across the continent.

***

Lance Young is the chief sachem of the Nemasket Nation, Wolf Clan, and chairman of the Nemasket Tribal Council. He is a 10th generation great-grandson of the squaw sachem Aime, daughter of the chief sachem Ousemequin Massasoit of the Pokanoket, father of Metacom King Philip. He lives in Medford, Massachusetts, and is the director of marketing for a technology consulting firm.