three women of hassanemesit

The record of the moment when Nipmuc George Muckamaug became a full member of the Hassanamesit congregational church in 1738. Image: Hassanamisco church book, 1731-1774, Church of Christ in Grafton, Mass.

The second church at Hassanamesit, a Nipmuc place now known as the town of Grafton, gathered in December 1731, and that’s when its church record book - my main source for this story - begins. Church records are unique among New England colonial records because they do not focus on economics when describing Indigenous people; the land sales, debt, and poverty Native people experienced because of English rule are wholly absent from the carefully inscribed testaments of church life. In Congregational church records, Indigenous people’s spiritual journeys and milestones were preserved and honored, and their births, marriages, and deaths solemnized.

While many Congregational ministers were prejudiced against Indigenous people, and expressed that racism freely in their private journals or letters, and even in public speeches, that racism did not carry over into the church record book. Indigenous and Black people are always identified as such, revealing a basic English need to segregate, but the experiences of those Indigenous people are neither denigrated nor judged. English and Indigenous people had their children baptized at the same time, during the same hour, and their names were joined in a single record. Indigenous people’s weddings were recorded on the same page as those of every other newlyweds. Their baptisms, communion, embracing the covenant - all were recorded on pages dedicated to the life of the church as a whole.

Here, using the church records in Hassanamesit, we explore the stories of several Nipmuc people in the mid-1700s, all of whom were born into or connected by kinship with the Printer family. The Printers took their name in honor of James Printer, who attended the Indian College at Harvard, was apprenticed to the printer in Cambridge, where he helped John Eliot translate the Bible, and risked his life to protect his kin during King Phillip’s War.[1]

We gain a rare picture of Indigenous life having nothing to do with economics, but with the faith decisions of three Printer women and their families: James Printer’s nieces Sarah Jr and Abigail Printer, and their cousin Sarah. All three were around 14 years old and living in Hassanamesit/Grafton when the record of their relationship to the Congregational church began.

Choosing church belonging

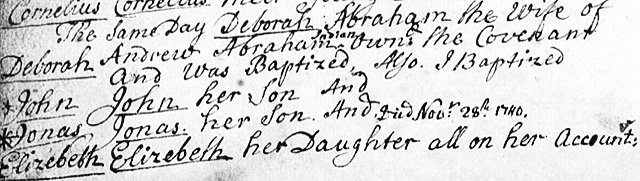

The first Indigenous name appeared in the church record on April 30, 1732: “Andrew Abraham Indian Jur. Owned ye Covenant And was Baptized” by minister Solomon Prentice (H/G 13).[2] Andrew Jr.’s decision to join the second church, which included none of his neighbors or kin, may have been a difficult one. But it’s possible that he had crucial support: the Hassanamesit/Grafton church record book tells us that ten months later, on February 4, 1733/4, Andrew Jr.’s mother Deborah also joined the church:

Deborah Abraham the Wife of

Andrew Abraham ^Indian ownd. the Covenant

And was Baptized Also. I Baptized

*John her Son And

*Jonas her Son. And (Died Novr: 28th. 1740.)

Elizebeth her Daughter all on her [Deborah’s] Account: (H/G 16 – emphasis added).

Perhaps inspired by Andrew Abraham Jr.’s example, another Nipmuc man, George Muckamaug, joined the church on January 5, 1735/6: “George Muc’kamuck Alias Read an Indian Man Aged 20 yrs Owned the Covenant here and was Baptized per me S. Prentice” (H/G 21). George went a step farther than Andrew and became a full member of the church two and a half years later, on June 18, 1738: “George Mucamug alias Read an Indian Man Ætat. About 22 or 23. years was Recd. to full Communion w this Chh” (H/G 34).

George might have served as counsel to Sarah Printer, Abigail’s teenage cousin and the next young Nipmuc person who decided to belong to the church. Sarah also “owned the Covenant, & was baptized” just six months later on December 31, 1738 (H/G 26). Sarah’s decision to join the second church was likely made easier by the presence of her friends and kin Andrew Abraham Jr. and George Muckamaug.

Different choices, blended families

Abigail Printer married Andrew Jr. on February 29, 1739/40: “Andrew Abraham ^Jur. (Indian) ^(both of this Town To Abigail Printer Indian”[3] (H/G 63). Their marriage was recorded on p. 63 of the church book, along with that of 15 other newlyweds.

Andrew Abraham and Abigail Printer must have known each other all their lives, and despite her decision not to belong to the church, it seems that Abigail was comfortable with Andrew’s evidently devout Congregational practice. Six months later, on July 13, 1740, her new sister-in-law Elizabeth Abraham became a full member of the church: “Elizabeth Abram Daughter of Andrew Abram Indian was Recd. into full Communion w this Chh” (H/G 35). Almost two years later, on May 17, 1742, Andrew Jr. and Abigail baptized their son Jonas: “Son of Andrew & Abigail Abram Jur. Indian on his Account” (H/G 36). Because Andrew Jr. had joined the church in 1732, his son Jonas could be baptized as an infant even though his wife Abigail remained outside the church. Their second child David was also baptized, but not their third son John, born on June 10, 1747.[4] Why not?

It may have been that Andrew Jr. was not in Hassanamesit when his son John was born. Abigail was not a church member, so while this baby was surely welcomed into his Nipmuc family in other ways, he could not be baptized without his father present. If Andrew Jr. was absent, it was probably because he, like his church brother George Muckamaug, had already left for military service with English forces in King George’s War. Both men died in that service. George’s date of death is unknown; Andrew Jr. was reported dead on August 31, 1747. Abigail’s grief might have been compounded by concern for her mother, Sarah Printer Sr., who was suffering from a long-term, disabling problem with her leg. Sarah’s husband Ami Printer Sr. had died in 1741, so Sarah Sr. may have been living with her daughter Abigail, both to comfort her after Andrew Jr.’s death and to receive care.

Their losses and illness likely led the two women to petition the General Court in October 1748 to be “empowered” to sell some of the land they belonged to and legally owned. Sarah Sr. and Abigail, identifying themselves as “widows & Indians of Grafton,” petitioned to sell two 30-acre lots out of their “valuable estate of land” that were judged by the Court to be worth £150.[5] Sarah Sr. and Abigail, neither of them literate church members, signed with their marks.

It was the first in a series of land sales by the Printer women. Just over two years later, on January 9, 1750/1, Abigail Printer Abraham and her sister-in-law Elizabeth Abraham each petitioned the court separately to sell part of the land they were to inherit. Elizabeth’s petition to sell her “aged mother” Deborah Abraham’s land was granted the next day, provided that “the house on the premises be reserved for the mother during life.”[6] Deborah Abraham had lost her son to “the service of the King.” Thanks to the Indigenous practice of leaving land to women, she could rely on her daughter Elizabeth to care for her, although it would come at the cost of selling part of their homeland.[7]

On May 4, 1752, Sarah Printer, Sr. and Abigail Printer Abraham sold 32 more Hassanamesit acres.[8] Perhaps Abigail sold this parcel of land in anticipation of her marriage to Joseph Anthony, which took place on November 14, 1752.[9] The money would have helped to guarantee a more stable future for the new couple and for Joseph, the son they welcomed just over a year later, on December 24, 1753.[10] It seems that Abigail’s mother Sarah Sr. opposed this sale, and perhaps her daughter’s marriage.

Surprising choices

If they were at odds in June 1753, we can only imagine the situation that Elizabeth Abraham and her mother Deborah might have been in at the same time, for nine months after the Printer sale we find this surprising entry in the Grafton town records: “Tommack, Andrew (alias Andrew Abraham), s. Sampson and Elisabeth Abraham, March 6, 1754” (1755).[11] Elizabeth Abraham, who had just turned 22 in February, had a child with a man out of wedlock. This is hard to account for given her commitment to Congregationalism and its clear prohibition on sex outside of marriage - this child, named after his religious uncle Andrew, could not be baptized even though his mother was a full church member. Elizabeth married Samson Tommack a year later, on May 30, 1756, when she was five months pregnant with their daughter Deborah; this marriage is only recorded in the town records, not the congregation’s records. She makes no further appearance in the records of her church, though she and Sampson continued to live in Hassanamesit/Grafton and to have another child, Silvanus, on March 3, 1761/2.[12]

Why did Elizabeth Abraham Tommack leave the church? Did she come to agree with her sister-in-law Abigail’s firm stance against belonging to the Congregational church? Or was it her new husband’s influence - did Samson lead Elizabeth Abraham away from her family tradition? When we recall the tremendous moment when Elizabeth was received into full communion with the church, on the basis of her assurance of salvation, it’s hard to accept either possibility. All we can do without further evidence is contrast her situation with that of Esther Lawrence.

Esther was the daughter of Abigail Printer’s cousin Sarah Printer and her husband Peter Lawrence. She became a full church member on July 27, 1755: “Esther Lawrance Inda. was recieved into full Commn. with ys Chh & baptized after her Confession of faith & Relation reced” (H/G 41).

This was just four months after her cousin Elizabeth Abraham had her son out of wedlock. We have to wonder what Elizabeth made of Esther’s decision to belong to the church, and how it compared with her own decision to leave it. This question is sharpened by the next entry for Esther. On January 11, 1761/2, she “made a publick confession for the sin of Fornication and was restored” (H/G 42). Fornication in Puritan/Congregational society has often been represented by authors and scholars as synonymous with the sin of adultery, but it was not. The church records of all towns abounded with regular entries for couples of all races confessing their sin of fornication and being instantly forgiven by their churches and their belonging “restored.” In almost every case, couples who committed fornication either had sex before marriage, as evidenced by the birth of a child less than 8 months after marriage, or had violated the terms of a fast day, during which sex was banned.[13] When Esther Lawrence made a confession of fornication on January 11, 1762, and was instantly restored, she was not yet married, so she wasn’t confessing to fast-day sex with her husband. Instead, the reason lies in a record just two weeks later: “Lawrence, Peter, s. Esther, bap. Jan 25, 1761” (H/G 97).

Like her in-law Elizabeth Abraham, Esther Lawrence had a child out of wedlock. Both women were full members of their church, and their pregnancies transgressed the terms of church belonging. But while Elizabeth seems to have chosen not to belong to the church by the time her child was born, Esther chose to stay. Her son Peter was baptized in the meeting house, and when she married Sharp Freeborn over a year later on July 6, 1763, minister Aaron Hutchinson performed the ceremony: “July 6 1763 Sharp Foreborn a Negro man of Licester and Esther Lawrence of Grafton an Indian woman were married together [in] Grafton pr Aaron Hutchinson pastor” (H/G no page).

This record of Sharp’s and Esther’s marriage is the last entry for an Indigenous person in the church record book for Hassanamesit/Grafton. Esther’s mother, Sarah Printer Lawrence, died in 1771. Her cousin, Abigail Printer Abraham Anthony Burnee, died in December 1776.[14]

Church records can never tell the whole story of the Nipmuc people who belonged to Hassanamesit/Grafton in the early- to mid-1700s and the decisions they made about love, marriage, and living as Nipmuc people. Nor do they tell us about the very real inequalities in life outside the congregational written record. But they do offer us the chance to look past economics to identity, to appreciate a rare testament of equality within the church body, and to get a glimpse of the Nipmuc people who made decisions about their faith and spiritual lives, and about belonging to the church gathered in their midst.

Notes

[1] The Printers were a Nipmuc family rooted in Hassanamesit. Naoas, a prominent man, had converted to Christianity and sent his son Wawaus (1640-1709) to live in an English household, where he was called James. James attended the Indian Charity School at Harvard College and became an apprentice to printer Samuel Green, where he became known as James the Printer or James Printer. He helped John Eliot translate the Christian Bible into the Massachusett language and actually set the type for Eliot’s Indian Bible (the first Bible published in the western hemisphere). James’ return to Hassanamesit during King Philip’s War, his determination to serve and protect his Nipmuc kin, his remarkable survivance during and after the war, and his role as a teacher and leader in Hassanamesit are well-documented, particularly in Lisa Brooks’ Our Beloved Kin. The English record is not explicit, but it seems that James had no children. Moses (1665? – 1729) and Ami (?-1741) may have been his nephews, cousins, or other near relatives who took his name Printer in James’ honor. “According to Nipmuc chief Cheryl Holley, James probably did not have children of his own, but his lateral descendants took his name.” (Brooks, p. 320) Moses and his wife Mary Pogenit Printer had a daughter Sarah (b. ~1715-20). Ami and his wife Sarah Printer had two daughters, Sarah Jr. (b. ~1717) and Abigail (b. ~1718). Each couple had other children, but these daughters are the inheritors of this dedication to the place the Printers belonged to that I focus on here. Moses Printer and his wife Mary Pogenit died in 1729, when his daughter and nieces were nine and ten years old. “Printer, Moses, - 1728,” Native Northeast Portal, https://nativenortheastportal.com/bio/bibliography/printer-moses I have relied on two sources for the Printer dates: Donna Rae Gould, Contested Places, p. 211. “Printer, Sarah” and “Printer, Sarah, 1717-1794” Native Northeast Portal, https://nativenortheastportal.com/bio/bibliography/printer-sarah and hthttps://nativenortheastportal.com/bio/bibliography/printer-sarah-1717-1794. There is some disagreement between Gould and NNP, but no major discrepancies. The record for Sarah, daughter of Moses and Mary, is unclear. The Native Northeast Portal lists four daughters for Moses and Mary: Elizabeth, Bethia, Sarah, and Mary, and states that when both parents died, “the children were bound out as apprentices.” “Printer, Moses, - 1728,” Native Northeast Portal, https://nativenortheastportal.com/bio/bibliography/printer-moses. The introductory timeline that begins Box 1 Folder 1 of the Earle papers confirms that “an Indian girl daughter of Moses Printer called Betty or Elizabeth put as apprentice to John Hazelton” and that in 1738 “Zachariah Tom had married Mary Printer d of Moses”. It does not specify what happened to Sarah, and we rely on both the NNP and Contested Places to tell us that she is the daughter to married Peter Lawrence. This means the part of the Earle timeline that says “Peter Lawrence m. d of Moses Printer” refers to Sarah, and not Bethia or Elizabeth. Earle Papers, box 1, viewer pp. 3-4 in viewer https://americanantiquarian.org/reclaimingheritage/sources/Papers_Related_to_Commissioners_Box1_Folder1/mobile/index.htmland Gould, Contested Places, p. 211

[2] For simplicity’s sake, all material quoted from the Hassanamesit/Grafton church record book will be cited inline as “HG page #”. All found online at “Church Records, 1731-1774,” Grafton, Mass. Congregational Church, New England’s Hidden Histories (https://www.congregationallibrary.org/nehh/series1/GraftonMACongregational4921). The page number refers to the number the minister wrote onto the page of the actual record book. As ministers often interleaved records and created demographic lists of births, marriages, and deaths in dedicated areas of the book, the page numbers I refer to in a chronological story will not always be chronological themselves; for instance, the February 29, 1740 record for Andrew Abraham, Jr.’s marriage is on page 63 of the Grafton church record book, while the record for his sister Elizabeth’s full membership five months later is on page 35.

[3] This doesn’t mean that the two were married by Prentice in the church. Marriage was transitioning in this period from the strictly civil ceremony it had always been for Congregationalists to a ceremony that ministers might conduct. Ministers made it clear when they were entering a marriage record only to benefit later records, when married couples baptized their children, and when they were recording a marriage they had solemnized by writing page titles like “Names of people married by me”, or by writing “by me” at the end of a record. Prentice does neither here, which tells us that the Andrews were married civilly, in keeping with traditional Congregationalism.

[4] Vital Records of Grafton, Massachusetts to the end of the year 1849 (Worcester: Franklin P. Rice, 1906), p. 9. The year 1747 must be an error, as Andrew Jr. wrote his will one year earlier, on August 1, 1746, and listed John by name: “my children Jonas David and John Abraham.”

[5] Martha was Abigail’s much younger sister, and likely Sarah Sr.’s last child.

[6] This note was inserted by the Trustees.

[7] This happened quickly: on March 11, 1750/1, fifty acres of “Elizabeth Abrahams Land An Indian of Grafton” were sold to Ephraim Sherman, “the highest bidder,” for £81.

[8] They sold to to Grafton buyers Joseph Batcheller and Jonathan Rolf for £60/5, “they being the highest bidders.” Massachusetts Land Records, 1620-1986, Worcester, Deeds 1747-1752, vol. 29-30, p. 512 [279 in viewer], https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9ZH-VD4G?i=278&wc=MCB2-1NL%3A361612201%2C361657501&cc=2106411

[9] Vital Records of Grafton, p. 157. The record says William, but subsequent legal documents call him Joseph, and their son was named Joseph, so I believe that was his name. Joseph Anthony was a Black man.

[10] Vital Records of Grafton, p. 12.

[11] Vital Records of Grafton, p. 130.

[12] Vital Records of Grafton, pp. 157, 130.

[13] When a church, town, or colony-wide day of fasting and repentance was called in the 17th and 18th centuries in woodland New England, people were meant to begin their fast the night before and continue it through the fast day. This meant both not eating food and, for married couples, not having sex. There was to be no pleasurable activity on a day dedicated to remorse for sin and a full sense of wrongdoing.

[14] She had married Sarah Muckamaug Burnee’s widower Fortune in January 1757/8.